My soul looked down from a vague height with Death, As unremembering how I rose or why, And saw a sad land, weak with sweats of dearth, Gray, cratered like the moon with hollow woe, And fitted with great pocks and scabs of plaques.

Across its beard, that horror of harsh wire, There moved thin caterpillars, slowly uncoiled. It seemed they pushed themselves to be as plugs

Of ditches, where they writhed and shrivelled, killed.

By them had slimy paths been trailed and scraped Round myriad warts that might be little hills.– Excerpt from “The Show” by Wilfred Owen (1918)

A myriad of “little hills” constitute the landscape of what once could be called Flanders Fields. One hundred years ago, the battles of the First World War marked the beginning of the change in landscape that we still bear witness to today around the small town of Ypres. The town, quiet and rather plain, discreetly reveals the scars of its past. More than 500,000 people lost their lives here and the entire western region of Flanders was reshaped by the war. From flat plains, sudden blasts carved out rough hills and deep craters, permanently altering the perception of the local landscape. The four years between 1914 and 1918 saw a political war as well as a war on the landscape.

Traces of the conflict can be seen around Westhoek, a region stretching from the coast of Belgium to the border of France. The horrific scenes of the past are in an uncomfortable way beautified by nature’s indifference – yet stories of land mines in local fields, mazes of old trenches beneath the soil, and human bones mixed with the earth still provide a narrative for visitors today.

A few kilometres south of the village of Zillebeke, in the area of Hill 60 sits a gigantic crater; the earth all around looks as if it were boiling as small mounds condense in some places and become smoother in others while old bunkers and remains of shells peep out from the ground. What was sculpted by a blast of 32 tonnes of explosives set to push back enemy lines is now nothing more than an out of place water basin in a small forest, known still as the Caterpillar. The no man’s land laid through the area was the narrowest in all the region, it’s even been said that soldiers could hear each other’s whispers from opposing trenches, leading tragically to heavier casualties.

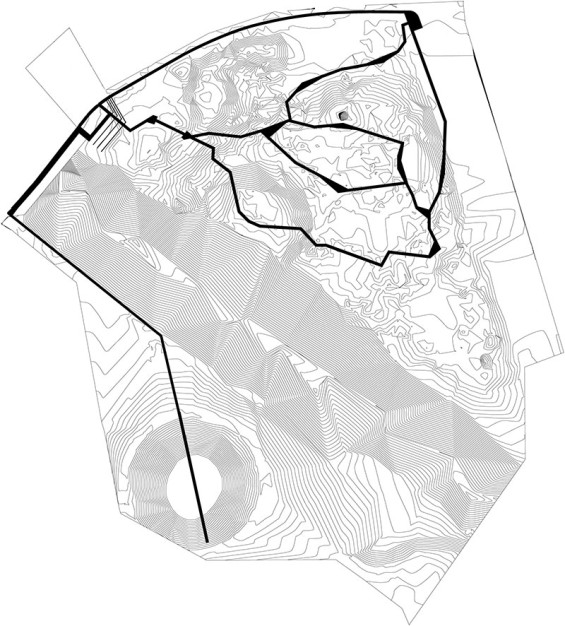

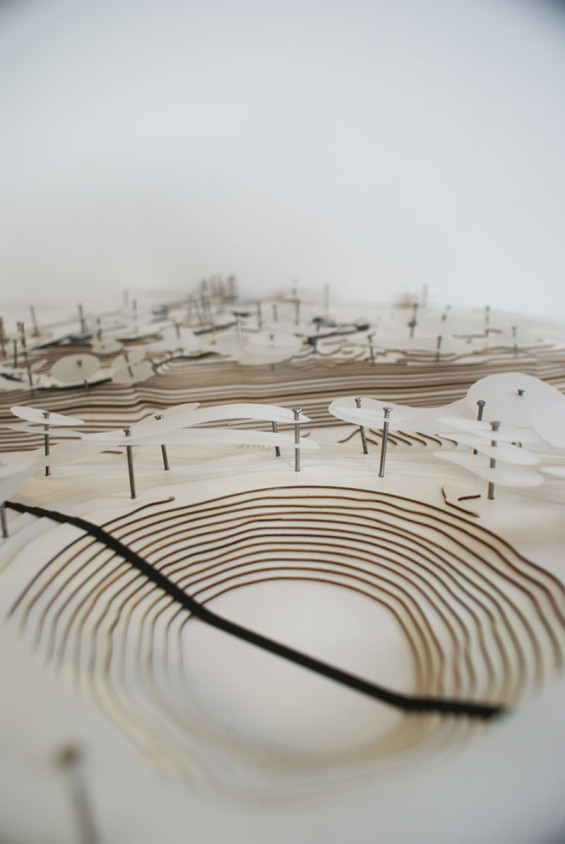

The important role these sites played in WWI now draws thousands of visitors a year to this region, urging the local municipality to revise the area’s tourist infrastructure. Hill 60 and the Caterpillar are two sites of the area designed by OMGEVING, a Belgian architecture and landscape office. The visually separated locations will be re-connected by jagged, narrow pathways that resemble the trenches that once filled the space, in addition to a widened bridge over the railway tracks set between them. The floating paths aim to preserve the earth beneath as well as lead visitors through the contemporary landscape. Yet the pathways also serve as barriers to the tangibility of the dirt one can now experience. The design strives after a principle of anti-intervention that allows the natural landscape to have the last word in what physically remains of the war. The pathway finally leads one to the depths of the Caterpillar as it descends along the crater’s slope, over the shallow water and up again the other side.

The topographic changes wrought by a series of major explosions during the Battle of Messines further demonstrate how the war left its mark on the land. A blast so terrific that it was registered in England, it forced the ground to shift to the periphery of the hit area. A geological event that usually occurs over thousands of years was imposed in a matter of seconds as hills suddenly appeared from the flat earth. What is visible today, after 100 years is only a peaceful pool surrounded by grassy hills and trees. With the intention of impressing the visitor with the magnitude of the explosion, the proposed design cuts a narrow path through the hill from the low-lying surrounding fields to the pool. One is literally immersed into the landscape, becoming one with the intensity of the past destruction.

What remains of the Ypres Salient is a striking area of dozens of seemingly disconnected sites. The history of WWI is kept alive in the common memory by local tours visitors through the most prominent areas, and signs pointing to numerous small cemeteries hoping visitors will come out with an enriched notion of the history behind the landscape. Now, one hundred years later, when all the human witnesses have perished, the landscape itself serves as the last witness able to give an account of what had happened here.

Understanding the role the landscape plays in teaching us about our common past, local municipalities and the Flemish government together with the office of the Vlaams Bouwmeester (Flemish government architecture advisory) commissioned a team, Gerust & Schulze Architecten and Lodewijk Baljon Landscape Architects, to define the conceptual framework for the area and to guide local actors in their efforts to reawaken the history of the Western Front. The team developed a masterplan for Memorial Park 14.18 that covers the area previously occupied by the Belgian, British and German armies. The small isolated cemeteries, post-war landscapes and monuments that are entirely visually disconnected today, are intended to be stitched together in a new landscape of remembrance.

Traditionally, memorial parks such as Chemin des Dames in France are constructed straight after the end of the war resulting in singular, often isolated and enclosed sites. The thematic monuments that garnish the post-war locations are usually dedicated to victims of a particular nationality and encourage the celebration of the heroism of their people. The ambition of Memorial Park 14.18 strives to go beyond political narratives and national pride, and instead reveals the impact of war on the natural environment, telling the story of the landscape itself.

Here, the post-war landscape is vast and so prominent that it appears as if it were always present. It meanders through and along the no man’s land despite artificial territorial boundaries. In the masterplan, the no man’s land is a guiding thread that helps visitors to navigate through the Memorial Park’s extensive grounds. Yet the no man’s land is in no way an actual path, it acts merely as a pivot around which all the other historical sites orbit. Rather than following a course of continuous narration, each site retains its own story providing only links to the other stories around the park. In this constellation of sites, the masterplan also incorporates modern structures such as utility poles, windmills and houses marking the juxtaposition between the present and the past.

War poets and the written memoirs and accounts teach us all the history of WWI at school. Through these, we get a glimpse of personal tragedies, moments of solitude and despair. But all along, the war itself had been writing with bombs and blasts in the earth, scribbling its message of destruction. Imprinted in the landscape are the many battles of the Great War. The immaterial memory of the War becomes physical once confronted with the post-war landscape in Flanders Fields, and it is this physical dimension of past conflicts that sticks to one’s memory the most.

WW I Memorial Park | Belgium | OMGEVING

Design Firm | OMGEVING

Text Credit| Kristina Camilleri-Grygolec and Karol Grygolec

Image Credit | OMGEVING