Authors: Nicole Tarrio and Zac Tudor (Arup)

All our towns and cities face the global challenges of urbanisation and climate change. With expanding urban centres, natural systems and processes have historically been replaced with grey infrastructure. With the climate and ecological emergency, surface runoff and the urban heat island effect are a pressing global concern. Do we continue to build bigger concrete tanks, or do we embrace natural systems led thinking that considers a holistic and practical approach to the design and management of our urban landscapes.

We must design our cities as a whole living system, bringing together natural and anthropogenic layers, including soils, vegetation, nature, sustainable development, transport and its people to create beautiful and functional landscapes in equal measure.

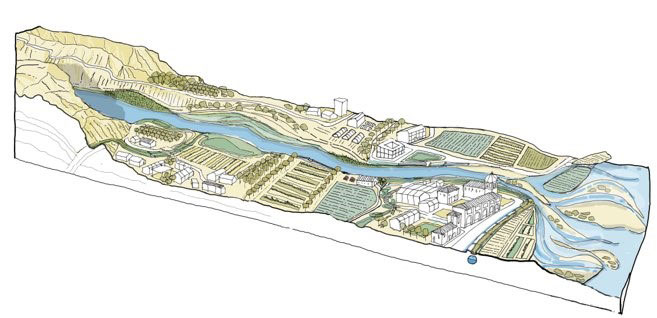

Due to their important role in climate resilience, there is a global shift to include Nature-based Solutions (NbS) in cities. The World Bank is one of many organisations that has recognised the significant importance of assessing and quantifying the benefits this brings to a city and its developments. Countries affected by extreme weather events are undertaking large investments. In Peru, the Authority for the Reconstruction with Changes (ARCC) is currently investing $4 billion over 137 projects, This includes flood prevention measures for 8 cities and 17 river catchments in which NbS is a major contribution to creating water-sensitive landscapes. In the UK, Arup’s pilot project with Severn Trent Water in Mansfield, UK is the largest urban sustainable project in the country. This project has explored an innovative approach allowing water companies to adopt and maintain these interventions as active flood assets.

Nature-based Solutions help cool our urban climate, increase ecology, reduce surface water lag times, and reduce the impact of atmospheric pollution. These adaptive spaces connect us to nature, and their changing seasonal beauty allows people to see our public spaces as integrated environments.

The opportunities for Landscape Architects to influence a more positive future through their work has never been so pronounced. From the outset of a project, we have the opportunity to inspire client groups and multi-disciplinary working to create a more sustainable, water-sensitive and greener outcome for public realm, transport, development and flood protection projects.

However, as Landscape Architects, we must ask, ‘When does adaptive and resilient design for the public realm become essential and not seen as innovative and a nice to have?’. Despite a growing recognition that the multifunctional public realm can have positive benefits for people and nature, there remain actual and, in some cases, perceived barriers that clients, disciplines and some designers feel cannot be overcome. These constraints can often include the following:

Perceptions and Barriers to Opportunity

Land availability & cost: One of the primary challenges to Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SuDS) implementation is the availability of space between the other demands and functions that the streets need to accommodate, making retrofitting for SuDS in existing infrastructure financially unviable. To address this, we need to recognise SuDS as critical infrastructure and identify suitable sites immediately. Financial incentives, tax breaks, or grants help encourage authorities and developers to adopt sustainable practices.

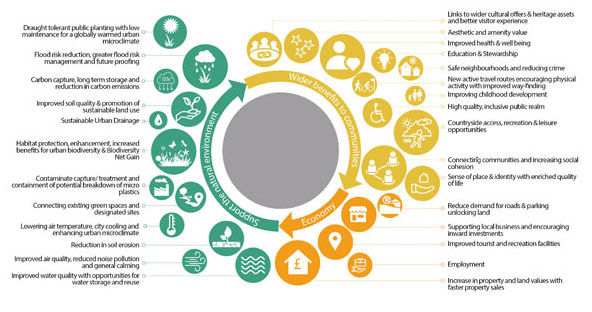

Financial barriers: SuDS projects often require significant upfront investment, coupled with the misunderstanding of the maintenance costs; they are often dismissed by private investors focused on short-term returns or authorities that have no long-term funding. Traditional drainage systems may seem cheaper initially, but they lack the long-term resilience of sustainable alternatives in terms of flood risk mitigation, water quality improvements and material durability. Green financing initiatives can address financial barriers, which can incentivise private investment and public-private partnerships to share costs and risks in sustainable urban development. Public realm schemes can, through good design, absorb many of the costs of a specific area. Long-term cost-benefit analysis should be emphasised to showcase the economic advantages of SuDS in reducing maintenance costs, improving social benefits, the wider environmental benefits, and enhancing property values over time. Below is a diagram of the multiple benefits NbS and, in turn SuDS can bring:

Public awareness and Acceptance: A lack of public awareness and acceptance of SuDS can hinder their successful implementation. Concerns over the loss of on-street parking, maintenance demands and poor visual appearance can lead to resistance from local communities. Educational campaigns and project-specific public engagement can help raise awareness about the benefits of SuDS. For public realm projects in local centres, such as Arup’s work in Hastings Town Centre and Greener Grangetown, SuDs are almost entirely welcomed, particularly when the community is involved in the decision-making process.

Technical expertise and capacity: The basic principles of SuDS can be easy to understand, however, the more detailed knowledge required to design systems to cleanse and store water and provide adaptive sustainable planting is more involved. Designing these systems without knowledge can, at best, reduce their effectiveness, resulting in a poor visual appearance, and at worst, supply no water management function. These factors of poor performance have the risk of non-acceptance by the industry. The visual failure also makes it harder to inspire and influence clients to adopt water-sensitive public realm design. Collaboration between academic institutions and experts in SuDS design can help bridge the knowledge gap and foster innovation in sustainable urban development.

Ground Conditions and Utilities: Poor ground conditions can reduce the natural effectiveness of SuDS. Lined systems, although not allowing natural infiltration, still provide storage, treatment and control of water movement through the systems. Experience has shown that a key reason, or excuse, for not designing with SuDS in the UK is existing utilities. Communication with utility companies and the local authority is essential to overcome perceived threats to their equipment. In most cases, pipes, cables and ducts can be incorporated into the build-up layers of the interventions without any detrimental impact.

Digital: Digital tools are valuable at all stages of our design work, from being able to undertake a site analysis, and helping quantify benefits and costs to aiding the long-term management of a project. The Mansfield project uses a data-driven digital tool to identify the best locations for thousands of SuDS, including rain gardens, permeable paving and bioswales, to be installed across the whole town. The catchment-wide approach seeks to reduce the risk of Combined Sewer Overflows (CSO) spills and will improve flood resilience of the local community.

Maintenance: Upkeep is perhaps the biggest barrier to the long-term success of public spaces, whether they contain SuDS or not. Ensuring the longevity and functionality of green and blue installations is critical for appearance and sustainability. Implementing maintenance plans at the early stages of the design that consider the next 10 to 20 years starts with functional soils and careful plant selection. SuDS systems become relatively ‘maintenance passive’ making inlets and overflows the only key considerations. However, the planting requires a considered regime and collaboration with knowledgeable maintenance contractors to keep the number of required visits to a minimum.

In public realm design, we should be celebrating our wilder places through function, materiality, and craftsmanship that is uniquely and identifiably of its place. In most natural landscapes, water plays a vital role in shaping and sustaining those systems, keeping nature in balance. So, in our towns and cities, why can’t we similarly celebrate water and bring balance to our urban water cycles?

Collaboration is key to bringing national, regional, and city-scale players together to develop a strategic integrated infrastructure plan. At Mansfield, unlocking multi-agency funding drew together water management with strategic transport, quality placemaking, and biodiversity improvements, resulting in further economic investment.

Landscape Architects must adapt to make our cities more resilient as our summers become wetter and hotter. Using drought-tolerant species, implementing SuDS, increasing canopy cover for shade and diversifying tree species selection in anticipation of an increase in pests and diseases will help future-proof urban centres.

A joined-up approach must be adopted, connecting to the larger natural systems that move through our urban fabric. With the increasing prevalence of flooding, urban water management is already becoming the principal consideration in our urban growth. If we can embrace, understand, and coordinate these benefits for integrating nature-based solutions into our public realm, it will set us apart as leaders in delivering hard-working green and blue infrastructure sustainably.

Authors: Nicole Tarrio and Zac Tudor (Arup)

Image Credits: As captioned.