Be’er-Sheva, the second largest city in Israel by area and the major city of the country’s southern metropolis, is unofficially titled “The capital of the Negev”. The Negev is the geographical region that belongs to the Global Deserts Belt (GDB), hence characterized by an arid climate.

In the past, Be’er-Sheva was situated on the boundary between semi-arid and arid climate. Today, however, due to global desertification processes the city is entirely a part of the GDB, which accounts for over 41% of the global terrain and inhabits over a third of the world’s population. The accelerating desertification has already harrowed large populations across many impoverished countries and now threatens another one billion people. These facts indicate the necessity for the development of Be’er-Sheva as the major city in the Negev metropolis on a local scale, and as a field of research for a global strategy.

Despite the increasing understanding of POS’ contribution to the city, they are allocated according to the standard as a function of population per square-kilometer, and therefore lacking in other planning parameters. While the global debate focuses on the problem of shortage in open-spaces within cities, Be’er-Sheva has numerous vast open-spaces that mainly suffer from a lack of quality, diversity, and uniqueness- leading to negligence and lack of attraction. Therefore this project included a vast research in which the main objective was to divert the emphasis from the quantitative planning-guidelines and standards toward understanding the urban functions of the public-open-space in its different forms, and toward examination of the parameters affecting the way its quality is perceived.

Be’er-seva’s POS’ – a history of suburbanization

Be’er -Sheva’s modern planning stems from Israel’s mass immigration in the 1950’s which floated the necessity for rapid accommodation. The Negev was declared a national priority zone for development, out of belief that this desolate region can lay the foundations for national prosperity. However, the planning was dictated from top-to-bottom, hastily conducted by planners who received their professional training in Europe and were influenced by European planning perceptions.

The first master-plan of Be’er-Sheva was based on the “Garden-City” concept: separation between residential and commercial or industrial areas. Independent neighborhoods separated from one another by green belts were proposed. Residential units were built in low density, and each neighborhood encompassed a small commercial-center that commemorated seclusion. Long, wide and winding roads divided the neighborhoods without any commercial building fronts or points of interest along them.

It soon became apparent that the Garden-City concept isn’t suitable for the desert-city. Ironically, the model that was initially made to heal the city of its illnesses has essentially drained the young city from all sense of urbanity. This problem was recognized in the 1960s, when a process of condensation has begun and is continuing today. However, large and desolate areas were left untreated and construction of massive commercial and employment centers in the city’s outskirts has led to the loss of urban vitality and the creation of urban-desert pockets. Various architectural plans were made for the city, yet the character of the city remains suburban and desolate. For the first time, this project suggests examining the suburbanization of the city’s open-spaces as a starting point for planning.

From research to planning

The research findings indicate that the urban contribution of the desert-city’s open-areas isn’t proportional to their abundance and vastness since many of them are perceived as low quality spaces. The finding that vegetation is the most significant factor in generating positive response demonstrates the importance of the garden in the urban texture. Another finding that supports this argument is that although residents mostly consume “paved” spaces adjacent to public and commercial areas, they actually feel better in the “green” spaces all year long. The factor that generates the most negative response is maintenance. The size and span of the open-areas, especially considering the desert climate and the socioeconomic profile of the city’s residents, strains the maintenance system. It seems as though many open-areas insufficiently utilize existing resources such as natural watersheds; many public buildings are adjacent to open-areas, but turn away from them, creating a “backyard” feeling. Moreover, most of the open-areas are neighborhood “pocket gardens” that aren’t exposed or accessible to passers-by.

The examination of the “grey” areas has surfaced missed opportunities. A functioning city is characterized by continuity and the connections formed by its streets. Be’er-Sheva, however, has no streets but rather wide and major roads that dissect the city. These aren’t in line with the common need for urban exploration, viewing and gathering. The cross section of the streets fails to create a pleasant human scale space. Furthermore, the roads in the city’s new neighborhoods were planned according to the Hierarchal-Roads model that also creates for pedestrian both disconnection and disorientation. The lack of urban leisure and recreation areas detached from commercial centers manifests in the consumption habits of local residents.

Considering the significance of the streets array in the urban tissue – and its poor urban functioning

And considering the significance of the open-spaces array – and their suburbanization and neglect,

What if the two were combined?

Detailed-planning

While the Garden-City plan aimed to create an oasis by annihilating the desert, the inspiration for this project came from the surrounding natural landscape. Analogous to the Negev’s flowing pattern of multiple tiny streams, the project suggests a master plan that bursts the suburban open-areas bubble into a flowing system. People flowing. A channel to urbanism. A platform to an urban oasis.

Relying on the research’s local-spatial and qualitative data system allows the creation of a master plan that suggests the reduction, prioritization and concentration of open-areas for the sake of efficient resource management as well as assurance of higher standards for their development

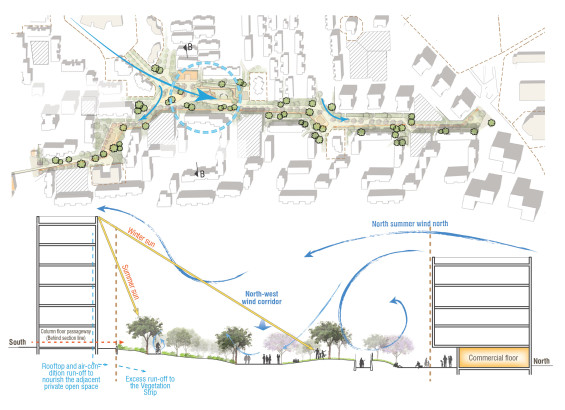

The detailed planning is based on a globally increasing planning trend that sees open-areas as organic leisure and socializing grounds, and therefore borrows the ecological concept of working with sequences. Working with sequences offers numerous benefits, nonetheless this projects wish to emphasize that the Stream sequence binds smaller POS’, public institutes, adjacent commercial paved areas, unbuilt areas, watersheds and more, into an inter-neighborhood entity and as such becomes an alternative circulation channel.

The assimilation of street characteristics into the garden made it possible to return to the principals of the organic street, detached from the chains of infrastructure and regulations, and more suitable for pedestrians. The combination of the organic street features with the qualities of the garden creates a defined public space that is dynamic and vibrant and offers a comfortable climate, biodiversity and diverse urban functions as an antithesis to the surrounding desert. It creates an urban backbone to which the potential energy of a planned and spontaneous interactions, group gathering and mixing of various communities, formal and unprompted activities drains into a flow of urbanism, as streams in the Negev.

As Streams In the Desert

Revision of the open spaces’ role in the desert city

Location | Be’er-Sheva. Israel

Designed by | Segal Lotem

Consultants | landscape architect Mueller Amir, landscape architect Berman Asif

Type | student final project. Technion – Israel Institute of Technology.

The Israeli Association of Landscape Architects annual competition – first prize (student category)

Annual students award for best final project – first prize