WLA recently interviewed Nic Odekon, a landscape architect at dwg. about his career and the future of the profession.

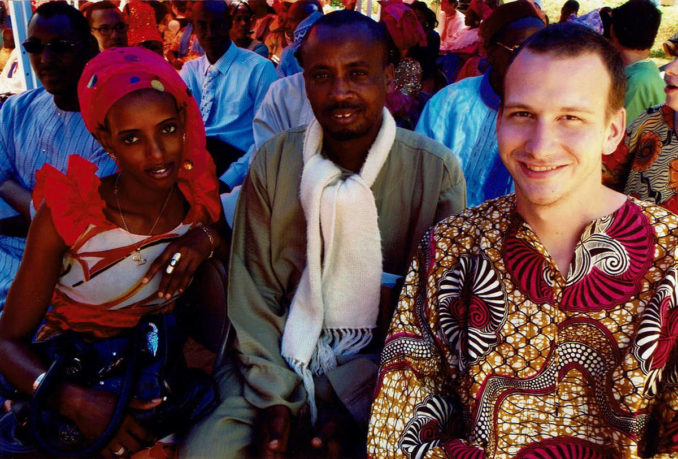

Growing up in Arkansas, I spent most of my time outdoors, exploring the Ozark mountains and the Ouachita Forest. Every other summer I would return to France to visit family, instilling a love of both American landscapes and European urban life. Stemming from this exposure to travel at a young age, I pursued international development through the Peace Corps after college and served in Kyrgyzstan as teacher trainer, then in Senegal doing environmental training with schools and women’s groups.

Following my return home, I went back to school to earn a Master’s in Landscape Architecture, being drawn to a profession that sits at the intersection of development, the public sphere, and environmental design and resilience. I am interested in the social dimensions of landscapes and the roles that they will play as climates continue to change.

I am an ardent believer in Type II fun – fun that’s miserable at the time and only fun in retrospect – and as such have taken up running, planning hikes through the national parks system, and trying to keep a yard full of plants alive in the Texas heat.

Why did you become a landscape architect?

Landscape architecture sits at several different crossroads: design, ecology, hydrology, soil science, development, and social policy to name a few. Ours is a profession of wicked problems and this is what first drew me to the profession after returning from overseas. I was looking for meaning and next steps coming out of the Peace Corps and landscape architecture resonated with me on a few different levels. The style of work seemed similar and there appeared to be a number of shared values between the practitioners of both sides. As I’ve moved from studying landscape architecture to practicing it I continue to find similarities, some more overt than others. The most significant overlap as of yet is the unique gratification that comes from taking a hairy problem, organizing it’s pieces to understand it, then presenting a solution to be applied. It’s even better when those solutions go on to work.

What is your approach to landscape design?

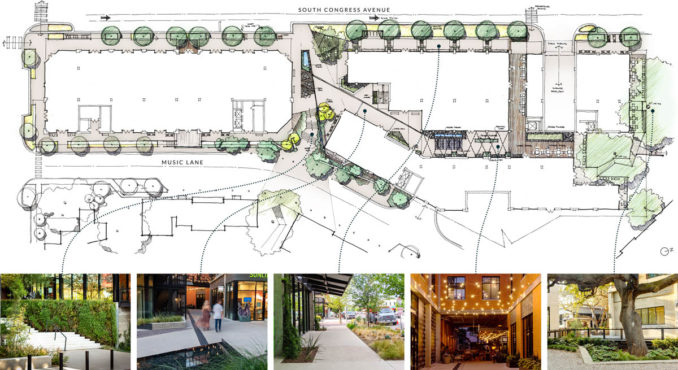

I am a proponent of telling the stories of the landscapes we design. There is a common appreciation for outdoor spaces, it’s not very common to find someone who doesn’t like flowers or shade from a tree, but attributing value and quantifiable benefits to something like a meadow has been more challenging, especially when it comes time to pay for it. Finding ways to best attach numbers to all of the intangibles built into our work has been a key part in the work that we do. A lot of my work recently has revolved around the documentation of project’s sustainability through programs such as SITES and LEED. Coming from international development, I would spend time on the ground with a community learning what would best help them and turning around to condense that information into a grant that would allow the work to be done. I see a very similar dynamic playing out now in landscape architecture. Landscapes are full of stories, ranging from habitats for humans and animals, to dynamic systems of water retention, seasonal variation, and ways in which these live designs hold up against change and the unexpected. Our design teams work to document aesthetic, functional and resilient projects and a lot of that work often goes unmentioned.

How do you see the future of landscape architecture?

I see landscape architecture as being the champions of common land. Our profession is known for advocating for the ecological benefits of landscapes, but these are not the only ways in which landscapes perform. Following the 2020 pandemic outdoor spaces have a renewed momentum as the social spaces and meeting places that are accessible to all, that shape the ways our cities are experienced, and that play a role in our collective health. That is not to say that we should abandon the ecological argument either, especially as we learn what climate change will continue to throw at us. Landscape architecture has more eyes on it now than ever in recent memory. By telling the stories of performative landscapes I believe we can increase the perceived value in landscapes and ensure that they continue to feature prominently in the development sphere.