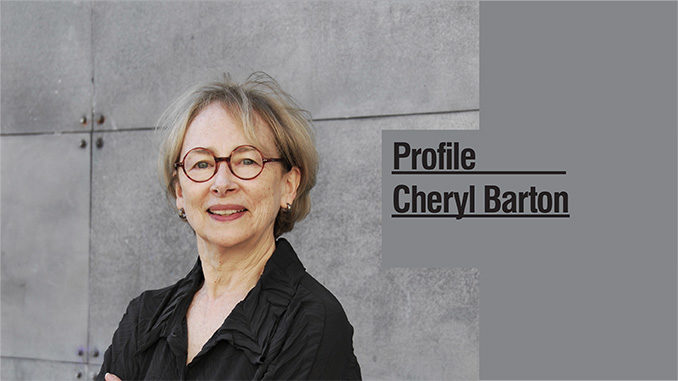

Recently we had the opportunity to talk with Cheryl Barton, Founder and Director of the Office of Cheryl Barton in San Francisco, USA. Cheryl leads the firm in the planning and design of revitalization strategies for urban and ecological systems – green infrastructure, parks and public places, institutional campuses and water-edge landscapes. She is internationally recognized for her leadership in the shift toward resilient futures – her award winning work integrates design innovation and adaptive systems thinking. Projects are commissioned by both public and private clients who are interested in building community connectivity, rehabilitating disturbed landscapes and deepening their relationship with the natural world. Cheryl sits on the Design Review Board for the Bay Conservation and Development Commission. She holds an MLA degree from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and is a Fellow of the American Academy in Rome.

Thanks to Cheryl for taking the time to answer WLA’s profile questions.

WLA: What made you want to be a landscape architect?

CB: Early immersion in the Eastern deciduous forest of Pennsylvania where I grew up was very influential in my becoming a landscape architect. I roamed woods and fields, watching seasons change, and delighting in the small ecologies of rivulets and ponds. This habitat gave me a core sense of the inter-connectedness of things — the inherently beautiful logic of natural systems.

In parallel, my grandfather, who had a deep respect for the environment, was a builder of carefully sited houses. I spent many hours on his construction sites sculpting sand piles and climbing through the open architectural framing. I learned that human spaces could be shaped and integrated with the landscape.

As my horizons widened, the circumstances of two landscapes had a profound effect on my understanding of the interconnected-ness of things: first, the Appalachian Mountains were being strip-mined with devastating visual, social and environmental consequences. When family vacations required travel through this wretched landscape, I would imagine and sketch alternative landscapes to repair and reconnect these places to their context.

A few years later, Lake Erie died. The Great Lake where I sailed and swam smelled of sulfuric acid and was dotted with rafts of dead fish. From an early age I understood that the environment was in a dangerous dance with certain aspects of human intervention and that a tipping point was inevitable. I felt compelled to intervene. But how?

In undergraduate school, I was curious about both art and science; I majored in fine arts and geology. I spent much time in New York museums and galleries and was inspired by and mimicked environmental artists in my work. Their interventions were seductive juxtapositions of elements and I saw immediately that they enhanced the presence of the receiving landscape. Art and environment suddenly became closely intertwined in my world view; I was thrilled by the creation of an environmental awareness through formal intervention. At the Boston Architectural Center I was introduced to, and later worked with, a master interventionist named Dan Kiley. After a few months working with Dan, his associates explained that he and they were landscape architects, not mere architects. This was a word combination I had never encountered. After two years in Vermont, I set off for Harvard to study this intriguing profession.

WLA: Describe your approach to Landscape Architecture

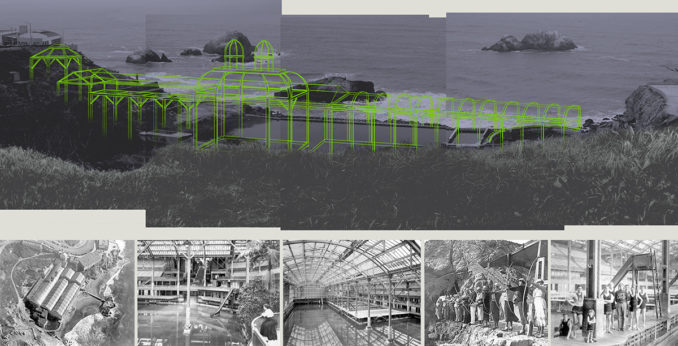

CB: Dan and I had a friendly ongoing ‘tabula rasa’ argument. He was in the ‘clean slate’ camp where a blank landscape would simply receive a design. I was in the ‘natural-cultural stratigraphy’ camp, where storied layers of each landscape give meaning to a place and its design.

I continue to work in ‘stratigraphy’ mode and have formulated a very personal operational Theory of HERE. Its tenets are:

- Here is not there.

- The circumstances of each landscape are like no other; it is informative and important to be where you are;

- Being where you are assumes a deep sensory awareness of place and taking the long view;

- Site-specific design is connected to larger systems thinking that is both observational and data driven;

- Scale jumping – a synchronicity of human scale and watershed scale – must be anticipated;

- Simultaneous optimization of present and future is anticipated; looking back to look forward is beneficial;

- Resilient design thinking is required to move beyond sustainable thinking.

My aim is to shape positive and healthy human experiences, by connecting citizens, developers, city agencies and institutions with the regenerative power of natural systems and inspiring places.

WLA: Where do you start with a new project?

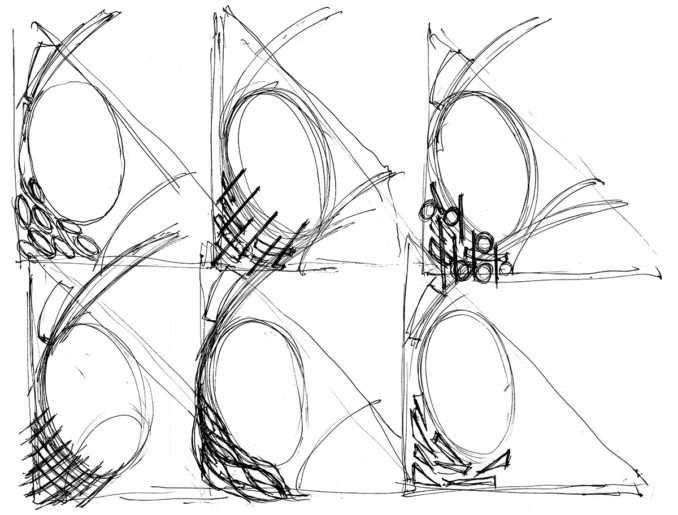

CB: I start by walking, driving or flying the site and its neighborhood and photographing it and its surroundings to internalize its physical circumstances and context. This is my initial source of inspiration. I ask questions and listen intently to everyone potentially involved in the project: clients, collaborators, users, donors, approvers and deciders. I research unanswered ‘design science’ questions – natural and cultural histories; topography, watersheds, water sources and quality, water tables, flood and SLR maps; soil chemistry and microclimate conditions. All of this builds a scaffold for design possibilities within which I let my imagination run to generate alternative schemes and strategies that I document with sketches, storyboards, photographs and words. Keeping the design exploration playful with crude study models that can be torn apart and easily rebuilt is a way I like to work with others. I generally start solo then pull in designers from my studio team and colleagues from other disciplines to challenge and clarify ideas and iterate design possibilities. Ultimately, the form and content of a design emerges.

WLA:What is the most rewarding part of being a landscape architect?

CB: The simple act of sustaining beauty is still rewarding. Our work endures as an art form that helps people see their environment differently and inspires rapture and deep connections to nature that sustain human life and culture.

There is great gratification in making one more positive impact on the Global Commons with every project: clean air and water, healthy soils, habitable cities and streets – things that are not commodities but are part of the larger public trust.

Landscape architecture has the power to transform attitudes as well as places at every scale. It is a stubborn yet optimistic proposition for resilience in the face of massive challenges and potentially massive change. Urban systems are being re-booted. Block by block. Street by street. Open space by open space. Landscape architects are (re)designing significant parts of cities worldwide as humane habitats, demonstrating that the integrated adaptation of human and natural systems – the creation of a Civic Ecology – is the answer to a sustainable future.

Find out more about the Office of Cheryl Barton