WLA recently interviewed Castiel Shepp, an Associate at Hansen Partnership, a multidisciplinary planning and design practice in Australia. Castiel is a landscape architect with seven years’ professional experience in local and international practice.

WLA | What made you want to become a landscape architect?

Castiel | I am fortunate enough to have been raised by two creatives. My parents met in Berkeley, California in the ‘70s, one a university professor of the arts, the other working within the arts and advocacy. Both fully immersed in and embracing of an era that encouraged personal authenticity, the stripping back of oppressive societal norms, an openness to cultural representation and for a life lived fully. Both incredibly driven, intelligent and charismatic role models who taught my sister and I that if you applied yourself, and your heart was in it, you could move mountains.

From a young age I’ve always preferred the picture over the word or equation. While a visual learner, I was fully aware that a purely creative career, in the simplest sense (artist) was not practical – being well aware of the struggles of traditional artists (i.e. both my parents). I knew that whatever profession I pursued, it needed to be grounded in more than just painting pretty pictures. But I also knew that to enjoy my work it needed to embrace my creative character.

I originally pursued a semester of interior design at the University of California Davis, which I found dull and restrictive. I was convinced this was due in part to the strong emphasis on maths (I’ve never been a fan) but more-so I felt creatively confined to a canvas comprised of four walls, a floor and a ceiling.

What I immediately loved about landscape architecture was the fluidity of both the canvas and the medium within which we operate – a la the natural environment. I also loved that it took place almost entirely outside. The following semester I broke free from the cube and enrolled in Landscape Architecture 001 Introduction to Environmental Design; and the fresh air and fresh perspective was most welcome.

In fairness to interior design, one could argue that most landscape architecture projects are also limited to a defined project boundary; however, I believe the impacts of our work can permeate beyond site barriers indefinitely.

WLA | Describe your approach to landscape architecture

Castiel | Pragmatic, detail oriented, sympathetic.

The technical side [of my approach to landscape architecture] is not terribly interesting – it comprises of honing the general skills a landscape architect requires in order to practice with a reasonable level of prowess and understanding. I also respect that to do any job properly you must have realistic expectations, not to say that this should flout creativity. What sets individuals in the field apart are the wheels turning in the right side of the brain – how we connect the dots and fill in the gaps after we’ve set out the base map, so to speak.

My design approach is also sympathetic to the qualities and purpose of place. I am constantly searching for organic ways to harmonise human use and the natural environment. I find that this relationship is most successful when the design is well-integrated with a site, so that the new infrastructure and its surroundings become part of a unified, interrelated composition. To do so we must respect and reveal the natural context and history of a site through a process of attentive observation, creative interpretation and innovative architecture.

This design approach often involves expansive research, illegible scrolls and rolls of trace paper before insight and resolution start to emerge and I maybe come up with something that might pass as a coherent, cohesive concept.

Rarely though does a project come to fruition that I believe is complete – there is always something that could have been refined. And that’s what I find exciting about landscape architecture – because due to the primary media we work with being organic living organisms, it’s never going to be perfect and will always be changing. And because of this dynamic process, the experience of a space will always be unique to the individual, at that particular time on that particular day, and is ever evolving. I pay attention to the details, and I design so that people notice the detail. I want people to engage with the space on an intimate level – to look up, down and around, to touch, to smell and to become familiar with the space on a personal experiential level.

WLA | What is the most rewarding part of being a landscape architect?

Castiel | I’m going to digress here for a moment.

A key driver of our work is to create visually beautiful places, as landscapes are most commonly experienced first and foremost by sight. While I must admit I scrutinise over perfecting the aesthetic qualities of a design; the picturesque is trumped when the landscape goes beyond first impressions and can trigger a deeper connection. Our senses are some of the strongest triggers of memory and emotion, and if we can harness these to reach people on a visceral level, I believe the value of the places we create becomes priceless.

Fostering an emotional connection is incredibly rewarding. For this to be successful however one must first have a comprehensive understanding of the elemental context within which they are working and the values of the communities they are working with. Never before had I fully appreciated the emotive connection a place can engender and the intrinsic values of place, until I was fortunate enough to work with the Traditional Owners of the land in Australia.

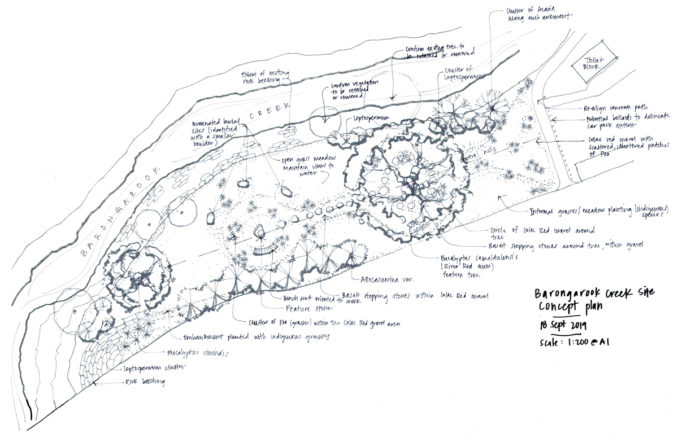

In 2018, our team was brought onboard a regional infrastructure project to regenerate a creek bed and reinstate associated park infrastructure following the construction of a new bridge – on the surface, a fairly straight forward design exercise. But once ground was broken our role quickly changed. Aboriginal human remains had been uncovered and work came to a halt. Following extensive consultation between the client, Council, authorities and the local Registered Aboriginal Party (RAP), we were subsequently engaged to prepare a concept design for an indigenous repatriation site along the creek.

I had a general understanding of the colonial history of Australia and the relationship with its Aboriginal communities (drawing similarities to that of the Pilgrims and the Native Americans in the United States). Upon my first meeting with John Clarke, a representative of the local RAP however, I quickly realised I had only scratched the surface.

Over the course of a few weeks, I engaged in intimate discussions with the Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation (the local RAP) to educate myself regarding the history, culture and pre-colonial landscape that was our project site. This education though was like nothing I had experienced when conducting project research. In lieu of sifting through strategies and discussion papers, I was being told stories. I learned that the Eastern Maar did not have a written language (when I asked how to spell their name), and that knowledge was communicated verbally, or through dance, art and sensory experiences. Above all I learned that the peoples’ connection with the land was intrinsic and deeply valued, and this relationship was often described as ‘connection to Country’.

I was saturated after only a few hours conversation, but I wanted to know more. How could I possibly have enough information to conjure anything meaningful? Before John left, he told me, should I wish to indulge myself beyond our limited conversations, to read the works of Bruce Pascoe in Dark Emu. Needless to say, I bought and finished the book that night.

As I mentioned earlier, I have a fixation for detail. The week following, I meticulously filtered through my scrawls and the earmarked book pages to identify the elemental and experiential components of place that could be condensed into a cohesive concept plan for the repatriation memorial site. I fully immersed myself within the site and its history. I learned that the ground used to be so soft with fine red dust that when one walked you couldn’t hear a sound. And that grasses did not grow en masse but sporadic patches so that one could walk for miles without having touched a single blade. These experiences invoked memories of place, and I knew that for this site to have any gravity, I had to tap into those sensory experiences. And given the palpable emphasis of connection and grounding, I felt it was only appropriate to work with pen and paper- my own subtle homage to the hands-on methods in which the Traditional Owners shared their stories.

A few months later, following an accelerated design and construction process (due to the sensitivity of the site), I received a message from John following a visit he took on site to inspect the works. He said, “It looks and feels perfect for what it is meant to be”.

As design professionals working within the public ream, we strive to improve the greater good by creating positive experiences within the landscape. It is our professional responsibility to value, protect and sustain the natural environment, and respect the values of those communities within which we operate. A successful project should speak to the needs and values of the community it is intended. As practitioners we need to be selfless, we need to practice restraint, and act with integrity and empathy – as we have the power to move mountains.

Text Credit: Castiel Shepp