OLIN‘s submission to the Living City Design Competition, has recently earned them the Cities that Learn Award from the International Living Future Institute and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The award acknowledges that OLIN’s proposal remained true to the project site’s rich, historical roots, and explored how social equity can lead to ecologically restored cities. The project team was led by OLIN Partner and Director of Research Skip Graffam, and included collaborators Interface Studio and Digsau. The team was one of six winners out of over 80 entrants from across the globe.

As Director of Research, Graffam viewed the competition as a research opportunity to inform future work within the OLIN studio. Since sustainability, regenerative green infrastructure and community engagement are increasingly vital components of the contemporary practice of landscape architecture, he points out, “This competition and its holistic approach to urban sustainability is really an early model of what landscape architects are going to be asked to do in the future.” He is confident that OLIN’s participation in the competition will contribute to a vital dialogue on the future of design, as greater accountability and integrated thinking will be necessary to change cities and communities for the better.

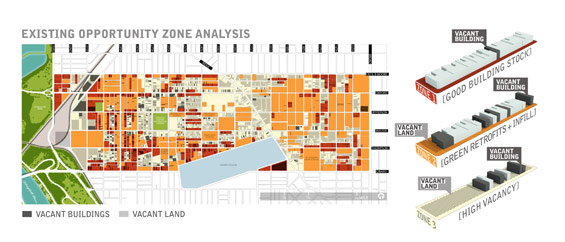

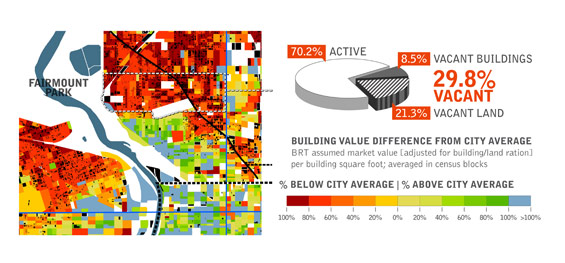

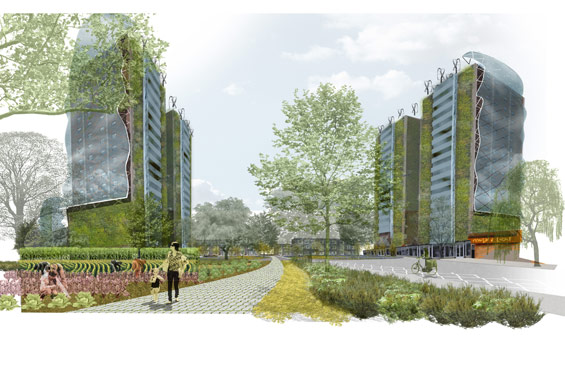

Patch/Work’s major focus was on scale and incremental development in order to render the site in a way that improves its ecological health, while keeping intact the historic architecture, street grid and overall character of the historic Philadelphia neighborhoods of Brewerytown and North Central. Rather than taking a traditional, linear master planning approach, OLIN’s unique concept of the “evolving block” phased in new infrastructure over a span of 25 years. The proposal evaluated regulatory strategies, planning incentives and political steps that would encourage and facilitate development, laying out a feasible plan for implementation that can be used as a model to inform real-life sustainable initiatives.Patch/Work creates opportunities, Graffam explains, from the “challenges resulting from the past 50 years of abandonment—inserting living systems into the block structure of the neighborhood and reconciling the rift between the urban fabric, nature, the energy grid and hydrologic infrastructure.”

Strategies for energy, open space, economic and social life, architectural development and water systems were integral to the success of Patch/Work. To satisfy the competition’s 100% on-site renewable energy demand for thousands of households, the team lined the commercial spine along Ridge Avenue with solar power-collecting canopies, and retrofitted numerous housing units with façades covered in photovoltaic panels. The team also devised a contiguous open space system, using vacant parcels that punctuate the blocks of row homes to create an integrated, pedestrian-friendly network of green spaces, populated by play areas, community gardens and urban farming. Existing row homes were examined for their potential to be retrofitted, renovated or replaced. The materials of structures deemed necessary for demolition would be reused elsewhere in the neighborhoods, supplying over 30 million bricks and three million square feet of wood for the building of new homes. To meet the net zero water requirements, the team aggregated the urban parks made of formerly vacant parcels to house district-level water treatment centers, and reconceived backyard alleys as new streets to connect the existing infrastructure. The long-abandoned Red Bell Brewery was refurbished to create local jobs and opportunities for locavore farming and consumption; this also achieved the competition criteria to provide 80 percent of the district’s food needs from locations within a 500-mile radius.

IMAGE CREDIT: OLIN, Digsau, and Interface Studio