‘Mā te kōrero, ka mohio,

Mā te mohio, ka marama,

Mā te marama ka matau,

Mā te matau ka ora.’

Through discussion comes awareness,

Through awareness comes understanding,

Through understanding comes knowledge,

Through knowledge comes wellbeing.

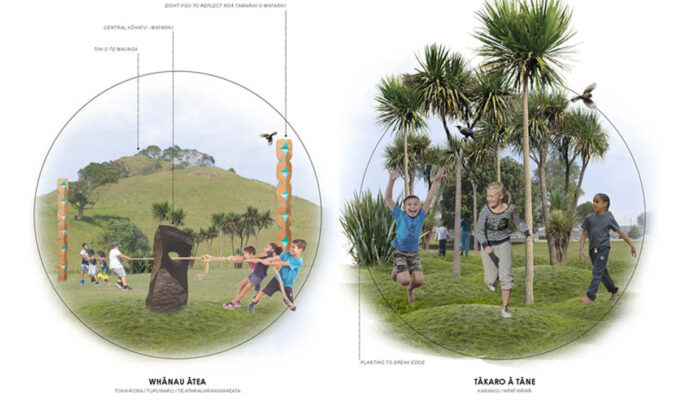

Te Auaunga (2018) stream restoration project included the first public installation of Te Mara Hupara (Traditional Māori Play) in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland). The success of that project has led to increased public awareness of Ngā Aro Tākaro (traditional Māori play elements) and interest in bringing these indigenous playspaces to more locations across Tāmaki Makaurau and beyond.

So, what are mara hupara and what is the difference – or is there one? — between mara hupara and what is commonly referred to as nature play?

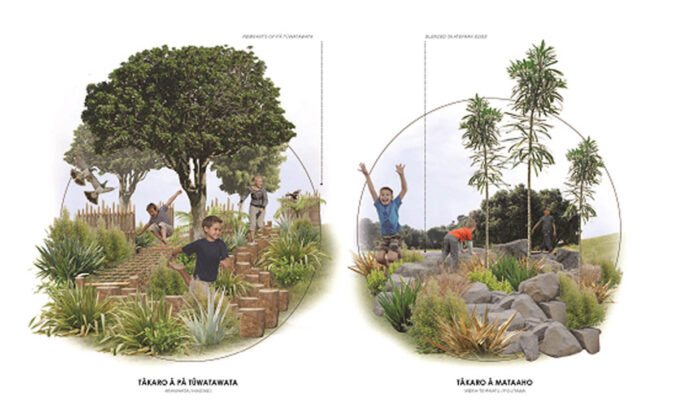

Storytelling and learning through play is a universal language through indigenous cultures around the world. Utilising Te Taiao (the natural world) – streams, trees, logs, and rocks – to create physical challenges through climbing, balancing and jumping is a timeless and universal activity. Adding meaning to play through imagination and storytelling is equally ubiquitous. Children around the world have been doing this for millennia.

In Aotearoa, acknowledging ngā kōrero tuku iho o ngā tangata whenua (the stories of the people of the land) and the wairua (spiritual) component of Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview) brings deeper meaning to both the activity and the object itself, and creates the difference between a ‘nature playspace’ and mara hupara.

“Instead of a child being read a fairy tale from a book, and then going out to play and pretending the tree in the front yard is a castle; with mara hupara there’s no separation – the story and the object are linked together, and together they create a spiritual connection back to the whenua (land) and to our tūpuna (ancestors)” says landscape architect Rangitahi Kawe.

It is essential to learn the pūrākau (cultural narratives) of the place and the people, and that can only happen through meaningful engagement with tangata whenua / mana whenua. It starts with listening and learning as landscape architects and mana whenua (Māori connected to a specific place) to work collaboratively through the kaupapa (process) and pūrākau to find the appropriate hupara related to each place.

Tangata and whenua are equally important, says landscape architect William Hatton; “each place has a unique whakapapa (genealogy) and can be represented through many mediums such as ngā aro tākaro.”

“However, you cannot have a co-design hui (meeting) and go through the process of collaboration on a mara hupara by a stream near the woods, and then months later simply replicate that design five kilometres away by the coast – even if it is in the same rohe (district or region)” he explains.

All whenua is different, and the pūrākau associated to them will be different; and from a design perspective, the natural elements will be different – so the appropriate hupara to reflect that whakapapa will also be different.

Dropping large boulders in the middle of a field, or putting reclaimed kauri on the beach, or a random row of timber steppers, has no meaning without whakapapa. It is the connection, and spiritual elements which define what mara hupara is.

“Listening to the pūrākau, finding ways to authentically express the themes contained in them through the selected ngā aro takaro, and also through the placement of the objects and the selection of materials and planting that surround them, is unique to each place and therein lies the difference,” says landscape architect Aynsley Cisaria.

“It starts with the kōrero. It is only hupara when working collaboratively with mana whenua,” says William Hatton. “If there is no mana whenua engagement, it’s nature play.”

That’s not to say that a nature playspace is a poor outcome, says landscape architect Aynsley Cisaria. “It’s not! Encouraging children to use their imagination and interact with water and the natural elements of the environment is a wonderful result. But you can’t call it mara hupara.” We have designed some challenging and imaginative nature play trails at Maygrove Reserve and for King’s School (2021) that celebrate the beautiful mature trees they encircle, but even though the raw materials of rākau (timber) and kōhatu (stone) may be the same as for a mara hupara, the lack of mana whenua involvement leading the narrative means the spaces are still just nature play.

Awakeri Wetlands (2019) utilises hupara by celebrating the star constellations meaningful to mana whenua. Unearthed swamp kauri on site have been relocated and placed strategically to tell the associated pūrākau about the heavenly realms and navigation. Although theses kauri may not look and act as hupara in the first instance, they allow mana whenua to connect with their spaces, reclaiming cultural identity and enhancing the mauri (life-force) of their takiwā (area).

Within two upcoming projects, we have begun to explore and interpret playspaces through both the traditional and contemporary lenses, working with mana whenua – to listen and learn about the pūrākau, and facilitating conversations and involvement with the wider local community. In doing so, we have been able to create rich and meaningful playspaces that are inclusive for everyone to gather, learn, celebrate, play, and connect to the whenua and the wider environment. Utilising kōhatu, rākau and aka (vines reflected through rope) to tell these pūrākau, these playspaces weave together hupara and contemporary play, creating a fusion of two world perspectives and a whole lot of fun!

Storytelling and learning through play is a universal language, says Rangitahi. So, providing an opportunity for the community to rediscover mara hupara is something to be encouraged.

“mara hupara are both a playground and a wānanga (learning space),” he says, “for tamariki, it’s a fun place to climb and jump around; for older generations, it’s about reclaiming spaces and bringing back memories. But the real connection happens when both of them are there together; and the history comes alive.”

We are grateful and humbled by the generosity and mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) shared by iwi, hapū, whānau and mātanga Māori (Māori experts) who continue to keep the ahi kā (the home fires burning).

‘Ehara i te toa, i te toa takitahi, engari he toa takitini.’

Our success is not that of our own, but that of many.