Welcome to Part 4, the final part in the four-part interview series that delves into the project work of graduating Landscape Urbanism students from London’s Architecture Association School. Read previous parts including Introduction, Part 1 – New Coastal economies, Part 2 – Urban Rewilding, Part 3 – Our Future Woodlands.

Introducing productive land into our urban areas

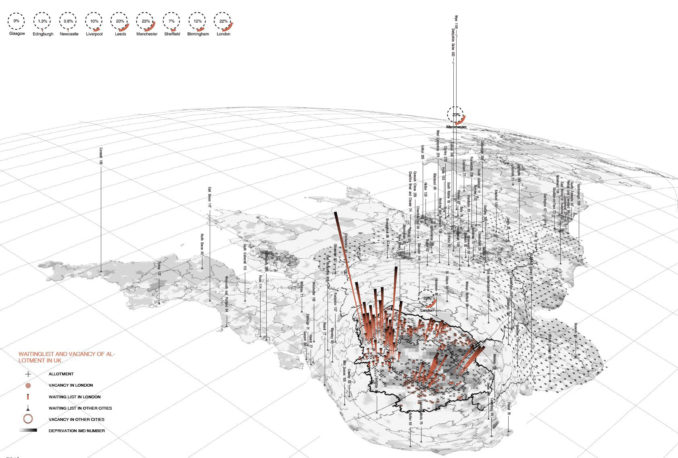

Long waiting lists and vacant allotments are part and parcel of the UK allotments system, with London and its high urbanization and subsequent land pressures being one of the most critical examples.

As the demands for private land ownership rise, so too does the value of land and with that comes the demand to utilise space once preserved for allotments for other more lucrative ventures. Equally as populations increase, and urban densification grows, the demand for allotments in our more populated urban centres skyrockets. Be it for the production of crops, the opportunity for a ‘patch of green’ or the social cohesiveness that comes with successful allotments, the popularity is continuing to increase.

Most allotments are heavily utilised. Vacancies are few, but if there are, it is usually driven by restricted access to water supply, bad soils or flooding risks.

How might one expand the opportunity for increased allotments? What could be done to afford more people access to more gardening activities within our urban centres? Is there a way in which allotments of the future can serve a wider group of overlapping users, and in doing so service multiple needs and demands concurrently? Is there another type of allotment that leverages land that currently has an existing use, but which could equally accommodate allotments? Is there a way to increase the value of the allotment land so that it can compete with alternate uses that vie to remove allotments in return for commercial benefit?…and importantly, is there a level of allotment activity that could be for the greater good of a city and not just the allotment ‘users’?

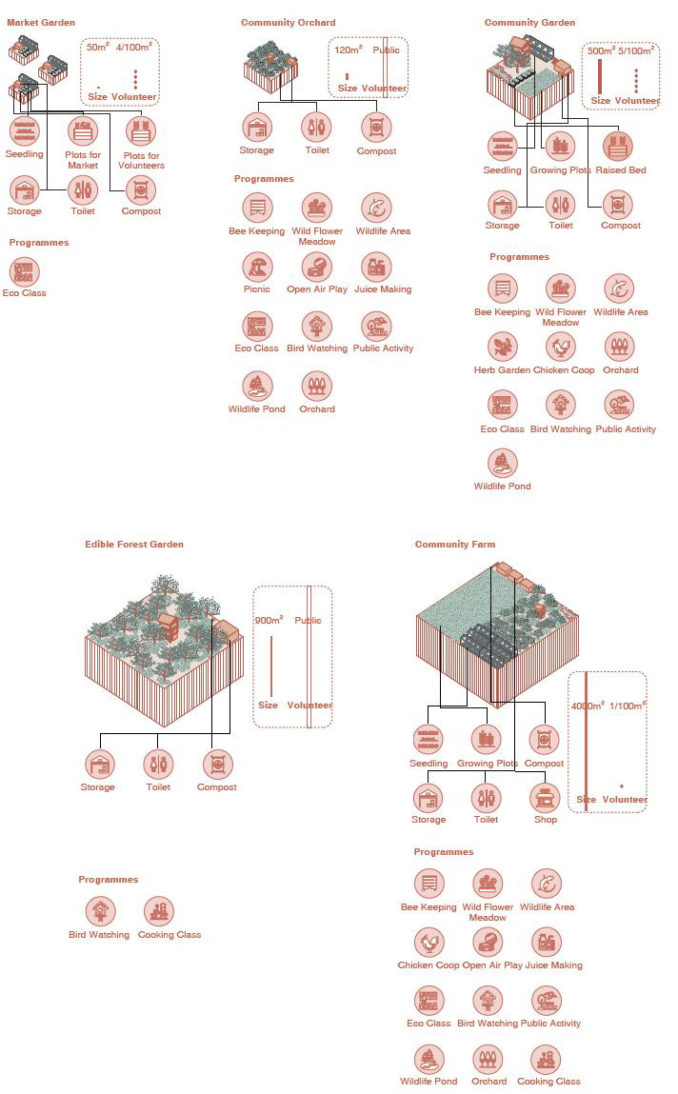

The edible landscape strategy proposed by this year’s graduating Landscape Urbanism students at AA school looked at just this – the growing of food in community gardens, allotments, schools and other public spaces as part of a wider and more integrated approach to urban farming. As a means of boosting local economies, providing local jobs (including training and apprenticeships) and thousands of community volunteer opportunities, the concept of an integrated edible landscape has significant positives and certainly worthy of delving into further.

Urban food growing achieves more than just homegrown produce and supporting community ground-up programs. There are proven environmental benefits, such as enhanced green infrastructure, increased city cooling and providing habitat for biodiversity. The examples found through Europe and the United States also provide a wide range of social well-being improvements such as small-business creation, community workspaces, local skills development and employment, social network environments, community-led regeneration, enhanced public spaces and a culture of sharing and unity.

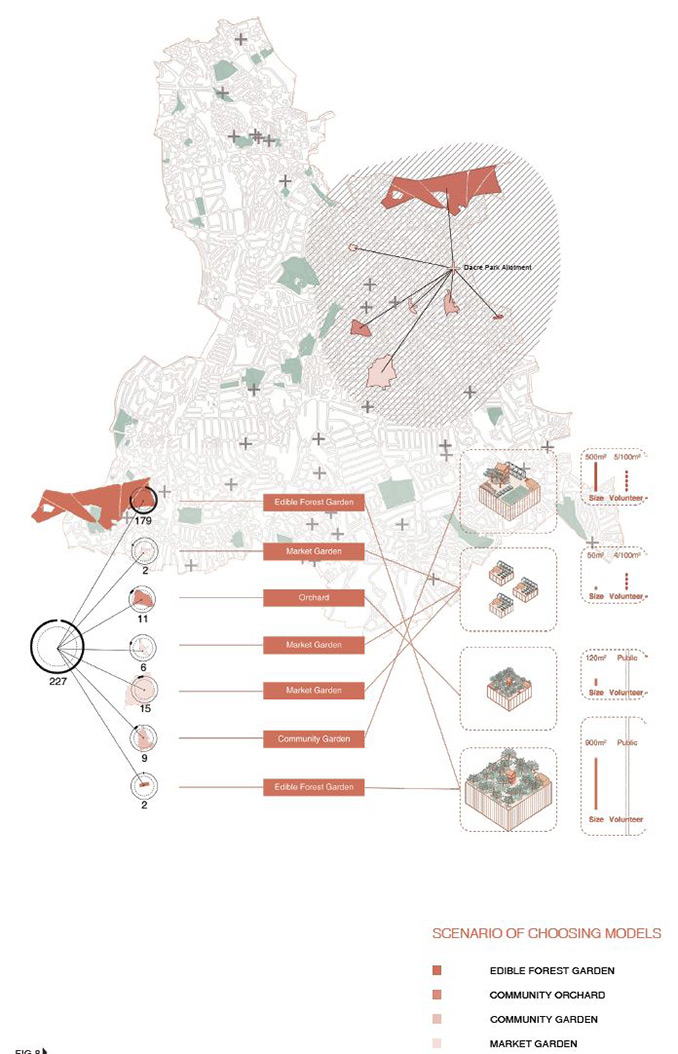

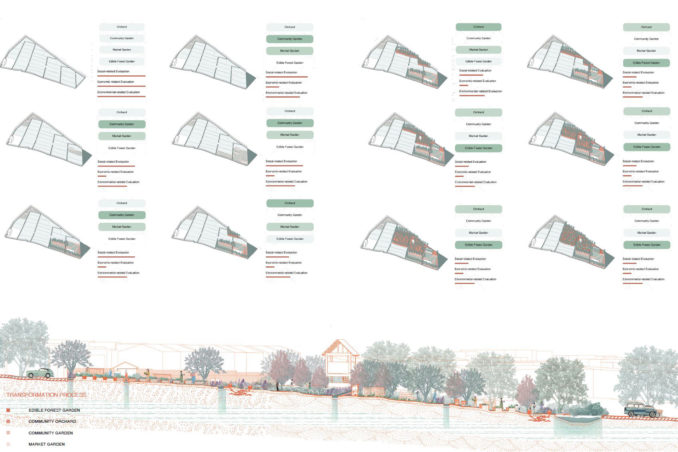

The Edible Landscape looks to provide a bridge between urban agriculture and the local economy and to empower communities on multiple fronts. Using the Lewisham borough in London as their project testing ground, the edible landscape proposes the transformation of existing allotments and adjacent school and community lands into a diverse agriculture model – one that is based on data that collates demand, demographics, and economic and environmental parameters.

Through the use of GIS the sites could be tested to determine the maximum utilisation of space, what spaces can best serve as agricultural lands, which parks could include orchard tree plantations, where community work sheds and learning spaces should be placed, what school and or other community lands could be leveraged for other community uses and or weekend markets, which locations can integrate local composting and recycling needs, and how to be achieve optimal servicing access, water supply and drainage.

This clever interactive tool has an end game though, one that is driven by a desire to support local social needs and to help build community. Through mapping the local allotment demands with that of available existing and newly repurposed lands, the tool is a guide for the council decision making when it comes to a wider social agenda around community, economy and wellbeing.

Interview A discussion between the AA Landscape Urbanism Graduating Student working group and Angus Bruce(AB), HASSELL Head of Landscape Architecture

AB: What made you focus in on this particular topic?

We came across allotments coincidentally during our studies and associated field trips. As our particular AA study group all came from China to study, we were intrigued with how the concept of allotments worked. We saw an opportunity to research the relationship between community, economy and environment worked – especially given the deep connection communities in UK cities have to ‘their’ allotments. We saw the long waiting lists, the separation by fences and barrier and the fact that allotments are classified as ‘public’ green space as topics that warranted deeper investigation. In China, although there is no allotment scheme, there is an emerging public landscape push for ‘edible landscapes’ within our cities. With agriculture being such an important part of China’s DNA, the push for functioning green infrastructure that provide food and diverse ecological values to cities and resident, is strong. We wanted to research if sustainable landscape practices such as this could be applied to an allotment model of the future..

AB: Did you spend much time with the local community and experiencing what they get from having access to allotments?

Of course. We put a lot of time into chatting with plot holders, interviewing residents living near allotments, watching how the spaces were used and looking into the ways other surrounding open spaces were functioning. We made sure to give time to receive community views and suggestions, to understand the related regulations, learn how different allotment scales and uses functioned, to look at creative models that showcase ‘allotment success’, and most importantly to appreciate the positive emotional connection people have to their allotment space and what it does to their health and well-being.

AB: Do you see allotments as garden or social spaces?

In our opinion, the UK allotment is a land of multiple attributes. It is an area where people gather together to plant. It has the planting attributes of the garden where people with the same interests bond and build community and add a social value to the neighborhood. They provide a platform for communication, engagement and key social activities. Whilst planting is the inherent function and original intention of the allotment, it is the social value that they provide that is of greater importance to these spaces – and this is where we focused our project

AB: You talk within your study of the idea of utilizing other public and community lands such as schools and churches as a way in which to expand community food capacity and broaden the social outreach opportunities. How receptive do you think the owners of these lands would be to this use occurring on their property?

For true community land, if the way the land is used does in fact benefit to the community, we would like to think that the project would succeed. Why not utilise residual land around churches for fruit trees, or introduced raised vegetable planters through school carparks or make dormant land between the frontages of social housing and the street as patchwork gardens? From a funding perspective, to help enable these initiatives, there are a raft of councils and community charities such as the National Lottery which would provide financial support, if the work is clearly for social benefit, and especially if the people involved are volunteers sourced from the allotment waiting lists.

AB: I was intrigued by the idea of an edible landscape and not just that of allotments producing foods for the allotment ‘owners’. Do you feel the community would embrace such an open egalitarian approach to food production?

We think we need to be clear here on the premise of allotments and the planting of wider community lands – what is the purpose of the planting? If it is primarily about food production, then the notion of egalitarianism is not feasible. But if the main purpose of allotment and community land planting activity is to promote community participation, then we believe communities will work together without distinction between ‘you and me’. In the process of planting, social interaction and communication will increase greatly, building networks and enriching neighbourhoods.

Footnote: Text and questions for ‘Allotments of the Future’ has been based on ‘The Edible Landscapes’ project work by AA Landscape Urbanism 2019 graduates Yuxi Tong and Wanxin Li, in conjunction with ©AA School of Landscape Urbanism 2018- 19 and ©New Economics Foundation. All images and graphics are by the project team.