Welcome to Part 3 of a four-part interview series that delves into the project work of graduating Landscape Urbanism students from London’s Architecture Association School. Read previous parts including Introduction, Part 1 – New Coastal economies, Part 2 – Urban Rewilding.

Transitioning from fossil fuels to a renewables economy

In the South Wales Valleys, the mining of coal has fuelled Britain for decades, and in turn, given rise to an extractive system mindset for the region and its people.

Local natural resources have been ‘harvested’ and the materials exported for years, with employment and economic growth an obvious community benefit. As resources either become depleted or demands for them alter, or as technology and extraction process change, the natural assets of a region risk becoming a positive contributor to the economy for an ever decreasing few. The locally extracted material serves fewer locally employed people, adds less and less to the economy of the immediate region and provides little social value return to the community. As was the case for the South Wales Valleys, with the closure of mines in the 1980s came a significant transition for the towns, to the point where they are currently defined as having the highest deprivation levels in the UK.

Whilst there has certainly been a shift in the region over the years away from mining and towards agroforestry, this change to a ‘greener’ veil hides the continuation of business as usual. One where regions are seen as primarily a resource-rich environment ripe for extraction and, as is the case for the Global South, missing a bigger picture approach to community needs and the growing push for self- sufficiency and township resilience.

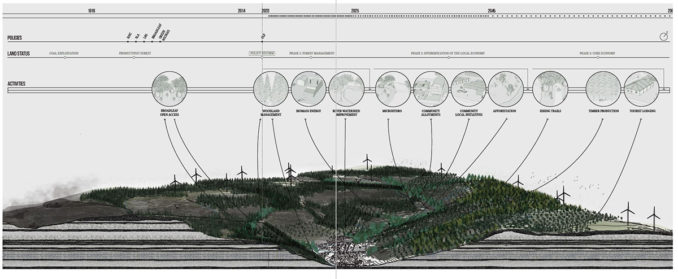

A student group from this year’s graduating Landscape Urbanism course at the AA School interrogated and re-thought a community forestry model in the Valleys, where the challenge of environmental forestry conservation empowers local voices, re-designs a new relationship with their landscape commons and proposes a model for the ‘future woodlands’ that could be emulated nationwide.

In collaboration with Welcome to Our Woods – a community forestry project – the focus study proposed a case-specific way of achieving a true transition for the region, from one extracted material to another, but done in such a way as to avoid the typical top-down approach, and aimed at building social, community and local economic resilience.

This project evaluated, as its starting point, the global implications of Britain’s transition to a green economy and how this process, using the existing natural resources, is able to be achieved for the Global South. Part of this was to also review and understand the regional and local implications of policy-making – specifically how policies shape the relationship between towns, communities and their landscape – and how this relationship is having significant social, economic, and environmental consequences.

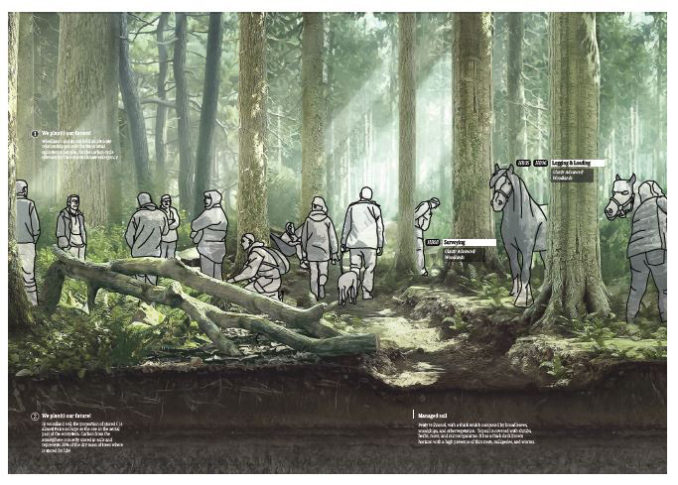

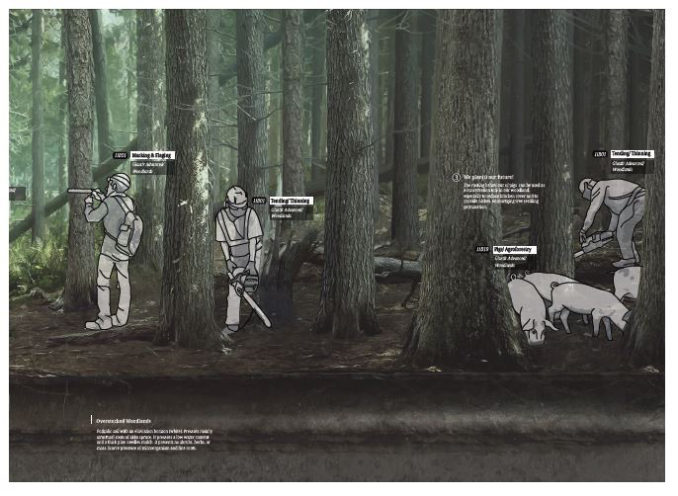

Through their work, the student group explored how the modification to existing policy frameworks could foster the positive development of a community-driven approach to forestry within public woodlands, administered under a ‘commons’ scheme. Working with the local forestry group, and utilising their deep knowledge and understanding of the working mechanics of how to care for a woodland, the design proposition proposes an approach that has the forests ecology and its overall health foremost in mind. This includes an artful and concise working manual on how to manage the pathways and forest trails, how to monitor and improve the soils health, to building a life cycle economy for the local community that treats the forest as a multi-layered asset and which elevates the woodlands to more than just that of agroforestry and a single source income. The approach manages to inter-twine natural processes with both productivity and environmental conservation and successfully proposes ways in which community-based initiatives can allow for the sharing of skills, knowledge, and awareness for the collective good of a wider community.

Interview A discussion between the AA Landscape Urbanism Graduating Student working group and Angus Bruce(AB), HASSELL Head of Landscape Architecture

AB: Your graphics are beautiful. Do you believe this level of detail and clarity is important to getting your concept across to a less design-orientated community?

The audience for architectural graphical production and visualization is very compartmentalized, because we always tend (mainly in academia) to abstract things, and in order to understand this translation you need to have a specific background or training. In our thesis, we work in collaboration with many disciplines and we are engaged with issues that matter at many levels of practice; hence, we need to move away from visualizations that are only understood by ourselves, and translate our graphical contribution as a social document, that indeed needs to be detailed so the specificity of the social, cultural, natural context can be interpreted clearly and be legible to any audience.

AB: Do you feel that your work will help this and other similar communities to take the concept seriously and that the approach can be more enduring?

This project proposition is very speculative at a level of governance, as we are rethinking the type of policies and schemes that might be needed to unlock a myriad of opportunities hidden within the landscape for the benefit of local communities; so we not only hope that the document could be taken as reference by communities but beyond that, by other political bodies in charge of the decisions that produce the landscape and, by the academia, so our education could be more committed and open to discuss the urgent global issues beyond the “architectural” scale.

AB: Is your proposition of how our future woodlands might work applicable beyond the South Wales Valley?

The proposed model indeed could be applicable beyond the valleys, but of course one needs to consider the skills, experience and interest of local demographics; and it does in many ways already exist in other countries with different forms of administrations. Britain’s long history of woodland management has gradually been supplanted by intense agroforestry, ending up with high soil degradation. This forestry farming model looks to build soil recovery practice, whilst satisfying social and economic needs of local communities, and at the same time helping to mitigate climate change.

AB: Is there a limit to how much woodland could be managed this way before elements such as tourism become diluted?

There isn’t a clear limit. The opportunity is endless, but we know that woodland management should start by benefiting the local community first before building tourism and or other economies into the model. Importantly, it is worth noting, that tourism done right should not disturb the woodland. It is a type of tourism where true ecological actions are valued and where the ‘visitors’ are allowed to experience the true essence of the woodland for its fullest value and aesthetics. It should become a source of revenue for local community to benefit from, and help build a circular sustainable model of land repair..

AB: You partnered with ‘Welcome to Our Woods’. Can you tell us a little more about them and why their work resonated with you?

We came across their project via Twitter @stickfarmeruk, where they shared how woodlands can dramatically impact the community through proper management and focussed design; and it was through their exception to conservation policies, that they have developed their project. Their work fascinated us because we shared the same vision about how policies design the landscapes we inherit and that we need to rethink these frameworks and push the existing boundaries to re-orchestrate this relationship between land, forests and community.

AB: How much direct community engagement did you undertake with your work and do you have a feel on how receptive they would be to such a concept?

For our project, we designed a business model that was informed by the community and around their specific intentions and skills – skills based on the management of the woodland and its sub-products – all targeted on framing the level and type of labour, infrastructure, and investment required. We constantly sent our ‘work-in-progress’ to them and they liked the final project work so much that they have requested copies to use in their actual woodland management works and to paste them in the walls of their offices and workshop; they loved the work as it very clearly graphically represents their intention of the last couple years and plans for the future.

AB: What is actually stopping this approach to forestry management becoming standard practice?

It has to do with the way woodlands are understood. Usually they are tagged as productive factories (plantations) with a monetary value mainly based on revenue from timber. The preference is for Spruce and other conifers species often planted as a monoculture for ease of harvesting and regulated growth rates. This monoculture approach allows for simple Clear-felling harvesting as the master-method of timber extraction. There are limited to no local native timbers and next to no value put to the soils or the native fauna and their habitat needs. Forestry as a ‘formal practice’ had been evolving with the main goal of producing as much wood as possible in the shortest timeframe, with little consideration on the multifold co-relations of woodlands with the quality of soils, water, air and even less interest in biodiversity and social impact.

AB: The core focus of mono species planting of typical agroforestry is single source revenue and restricted employment opportunities. Your proposed model seems significantly stronger on both fronts and I wonder why this isn’t a more obvious approach to our forests and woodlands and why it hasn’t already been adopted more broadly.

Monocultural forestry practices are purposed towards mass production of agroforestry products which leave the soil disturbed with no opportunity for carbon storage – but it also excludes community involvement. Our project approach proposes a model of woodland management that is certainly a slower process and requires community effort and participation, and which means a slower revenue stream – but this is not about the short term fix. This is a proposal that is focussed on longer-term investment in people, place, ecology and the planet.

AB: Typical the matter of soils in agroforestry terms are really only of concern as it relates to the necessary fallow periods required for successful future mono-species planting. You spent a lot of time looking at the health of our woodland soils at a wider more holistic level. Why do you see this as being important?

In temperate forests, as per what we have here in the UK, around two-thirds of the carbon sequestrated is stored in the soils of the forest, and the rest in the vegetation itself. Therefore, it is critical to protect and include soil in the whole dynamic design of the future forests to effectively engage with the climate emergency.

AB: What is your vision for the future of this project?

We would hope that the research conducted would act as a reference to community and government bodies in changing future forestry and woodland management approaches, across different scales..

AB: Where do you see yourselves next year now that you have graduated?

We are all from different backgrounds, working together within the same Landscape Urbanism course at the AA School, so our answers are varied. Some of us wish to use the acquired skills to help develop and bring forward global issues through digital mappings and cartographies. Others of us want to keep working on interdisciplinary projects, where our expertise in soils, geology, and environmental research take a proactive role in grounded projects – All of us though are focusing on applying design to the climate emergency context.

Footnote: Text and questions for ‘Our Future Woodlands’ have been based on ‘The Just Transition’ project work by AA Landscape Urbanism 2019 graduates Yasmina Yehia, Rafael Martinez, Elena Suastegui, in conjunction with the ©AA School of Landscape Urbanism 2018-19 and ©New Economics Foundation. Images and graphics copyright is held by the project team graduates.