Welcome to part 2 of a four-part interview series that delves into the project work of graduating Landscape Urbanism students from London’s Architecture Association School. [Read the Introduction or Part 1 – New Coastal economies]

“Many cities are challenging places for wildlife, full of people, noise and pollution. But small changes are all it takes to tempt many species to live in the concrete jungle” Martha Henriques_BBC Future

Urban rewilding, as a term, includes those initiatives or programs that seek to encourage biodiversity, ecosystem function, and the persistence of native species in a range of urban settings, including on private and public land. It is meant to be a progressive approach towards natural restoration that contributes to habitat expansion, brings back wildlife and reconnects human activities to nature. But how much of this is in fact geared to improving areas outside those regions at the fringe of our cities and where nature and its processes are already taking hold, and/or, have not quite yet been eroded? How can we challenge our design thinking within the city limits and look to including rewilding of our urban environments as a key part of the design process?

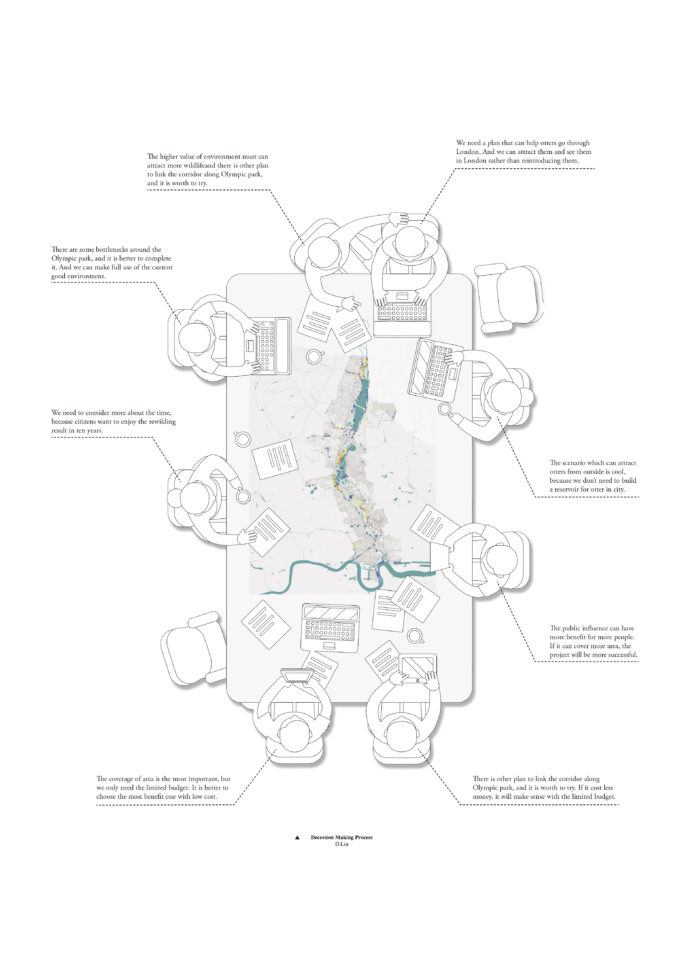

The Urban Rewilding project proposed by a team of this year’s graduating Landscape Urbanism students from the AA School looked to unpack these questions, and devise a method by which designers could help to bring true nature into our urban environments. The team built a collaborative decision-making tool that evaluates various site scenarios according to multiple social and environmental criteria, and in doing so help trigger a discussion among competing institutions, councils, agencies, specialists and locals involved in the decision-making of future urban rewilding project opportunities.

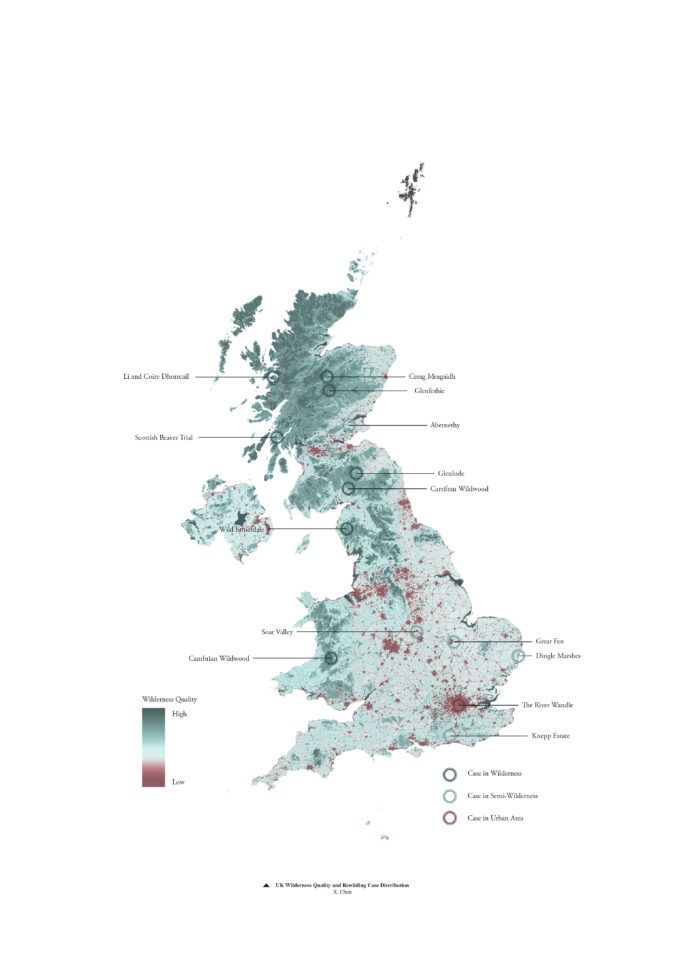

In their project work, which was focused on London’s Lea Valley, the student group researched the importance of keystone native species and the associated trophic cascade effect that comes from understanding the top predator necessary to bring about the ecological change being sought. Successful rewilding case studies throughout the UK, plus other examples such as Yellowstone Park in the United States and their reintroduction of the wolf, were used to help understand the various global methods of rewilding and their effects.

Across the UK most rewilding cases happen in remote areas, with very few urban examples due primarily to the various ecological problems caused by urbanization, such as reduced biodiversity and habitats. This doesn’t though have to mean rewilding can’t occur throughout the broader built environment, and nor should it. In fact, many of the problems that are seen as restrictions to rewilding in the city, are in actual effect able to be solved through the focused act of rewilding.

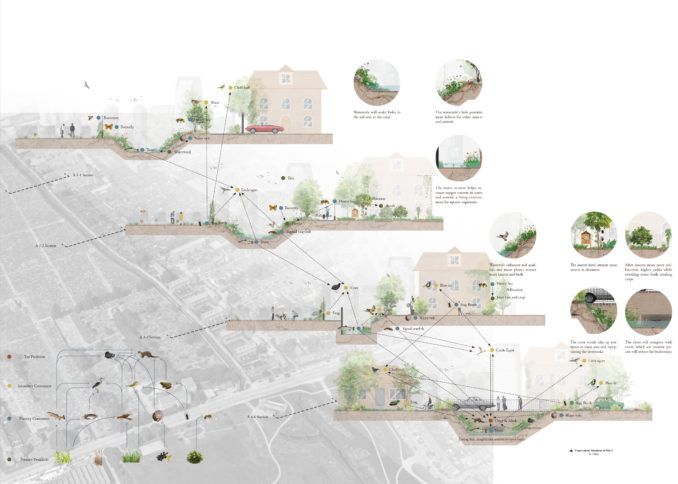

Not only does a rewilding approach bring about greater ecological value to our cities, but it also improves natural biodiversity of the wider region, improves water quality, increases groundwater, lifts living standards of urban residents and property values, and critically offers improved social and human well-being through more opportunities to connect with nature and lifts community education around ecology and nature.

The project teams data-driven decision-making tool analyses an existing unhealthy urban ecosystem and studies the proposed corresponding solutions focused on defining which keystone species should be proposed for reintroduction into a given project site. In the example of the Lea Valley project study, this keystone species was the Otter (Lutra lutra). Easy right, simply add them? Not so. Rewilding in the context of the city is far different from that of more remote areas. The competing human interests, overlapping authority policies and judicial boundaries creates a complex background that invariably competes directly against environmental factors and ecological intentions.

In order to find the right compromise between urban rewilding and different stakeholders’ benefits, the project team ensured social inputs were included within the data analysis, in equal measure to those of an environmental bias. In doing so they have created a ‘live’ tool for scientists, experts, institutions, residents and councils alike, that provides in one place the necessary information about cost, natural expansion and social impacts. The interactive tool creates different scenarios quickly and whilst users may not get the perfect plan, it does put forward the most acceptable solutions that work with the varied competing interests and concerns.

Once a plan of attack around rewilding of an area is devised, the simulation results are then tested on the real site survey data to check for obstacles to the on-the-ground application of the plan. This step also ensures there is an open dialogue around how to develop alternate interventions to address bottle-necks to the process. Once mapped out and tested and all parties aligned, the digital simulation of the rewilding project is used to calculate and predict the social value, environment value and ecological effect after the completion of different parcels of the works are completed.

Interview | A discussion between the AA Landscape Urbanism Graduating Student working group and Angus Bruce (AB), HASSELL Head of Landscape Architecture

AB: In most instances, projects that involve the idea of ‘rewilding’ are focused on rural, peri-urban and de-populated areas of our cities. Why have you focused your efforts on the more populated areas of a city, where urbanisation processes are most heavily concentrated?

The rewilding connotation is to reinvigorate the natural environment of a certain area and protect the wild species that originally lived thereby inspiring the power of nature. In the process of urbanization, the urban area happens to be the most damaged place in the natural environment and we believe that it is urgent that we begin to find a balance between urban development and natural restoration. Rewilding is a cost-effective method that can increase biodiversity and improve the quality of green space in terms of ecology and the environment. It seems rewilding is a good method to solve a raft of urban problems

AB: How do you propose that we break this urban-rural distinction and start to address ‘rewilding’ as a holistic topic?

There is no accurate boundary for rewilding because animals have different territorial awareness than those of us human. As humans we believe that the better starting point is within rural areas because we believe it is easier to build a big scale animal living spaces. But what then? We have proposed that wildlife and healthy ecosystems should be allowed to be expanded into the urban areas, and it is through green space corridors or ‘wild networks’ that we can attract them back to the city naturally.

AB: What do you see as the key blockage behind the idea of ‘rewilding’ our cities?

It’s all in the decision making process. At the moment planning approvals give little weighting to ecology and or the potential for new ecologies. It’s all about a better urban outcome in terms of built form and hard engineering and architecture. The community up rise of these last few years is very much about valuing the planet and protection what we have – and even enhancing it if possible. To take heed and to listen means to change the planning process to ensure the bigger global questions are asked, even at a local borough level. We need to open the city dialogue up to consider the environment in terms of real nature and full life cycle envriomental improvements. Not green ‘window dressing’.

AB: Current measuring of rewilding efforts are based around environmental indexes only. Do you feel that we should in fact expand this to include the social impacts of rewilding?

We strongly believe that its critical to start considering the social impacts, as we feel that this is the answer to finding the balance between multi-agency interests and community. Every different rewilding scenario will generate different social impacts and it is why our modelling indicators have given so much attention to social value..

AB: Are there current policies at local, regional and or national levels around rewilding? And should there be a shift in the current decision-making process to ensure projects have clearer expectations set around them when it comes to proper open space ecological planning?

Whilst there are some excellent rewilding projects happening in the UK with the support of Rewilding Britain and Bug-Life, there are limited actual policies and or clear description for urban rewilding nor the process around the decision making for such projects. The recent ‘Protection of Pollinators Bill’ put to the House of Commons last year is certainly a start in the right direction.

AB: In your work, you have compared national rewilding projects that link to existing areas of wilderness quality versus those that don’t. Why is it important to you that we consider opportunities for rewilding within our urban environments and not limit this effort to where we already have the start of a more robust ecosystem?

We think this question is somewhat similar to “why we chose cities rather than an existing wilderness as our project site”. It is true that natural wilderness area are better for rewilding projects than in the cities, which is one of the reasons why most of the rewilding projects are carried out in these types of areas. Urban areas though have their own ecosystems, and this ecosystem often faces more serious problems than wilderness areas because of excessive urbanisation. We want to use rewilding to restore some of the destroyed ecosystems of our cities and allow the re-entering of wild animals to their original territory. Its recognized that the bigger challenges for rewilding are in our cities, because of the complicated urban participants and mulit-layered policies – but if we can make sense of these problems through our study we believe it will be easier to apply the logic everywhere.

AB: Is your work applicable anywhere? Is the process the same regardless of the urban or peri-urban location? And is it regardless of the level of the ecological starting point of the site?

It’s closely related to the ecological level of the starting point. According to our tool logic, a better ecological starting point means more rapid and widespread impact, and lower upfront input cost. If we input data from different locations, we can try the rewilding project in other places. The logic will be the same, but the difference is that the digital model has a boundary but the reallocation do not have. It is the point that the tool cannot consider and the difference will happen in this aspect. The start point is also important because it will have an influence on the speed of impacts.

AB: How important is the social connection to urban rewilding for it to be successful?

We think it is the key point. If we cannot link the rewilding plan with something citizens are really interested in, there is no one will really care about the scenario. Except that, only do we have more social support, the plan would happen in practice rather only on the computer. Social connection is a key part of the project. It is not just about different institutional units making exchange decisions. It is more hopeful that neighboring residents can participate. After all, the process of rewilding not only changes the ecological environment and animal habitat, but also It will change the living environment and habits of the surrounding city residents, so letting different people participate will make this project more implementable.

AB: Reviewing the work and hearing you present it in detail, I wonder if this is just as much about ecology and rewilding of our urban centres as it is about managing government politics and competing human interests. Do you see this as the root of actual urban rewilding success?

We think the root of success is very much about ‘everyone around the same table’ and being fully informed. It helps of course if there is a natural asset within the city to work with. Assuming though that there is this environmental green space base, then having the various parties, government agency and community groups together, with the right data in hand is critical. Without this, both the environmental and social aspirations of a rewilding project will fail. Our working database model looks to provide the various users with this base material and allow them to have the conversation – they just need to find the table to sit around and make their plans!

AB: Finally, as you have presented, nature’s ability to endure over time is clear. Is our role therefore as practitioners within the built environment one of holding back the human pressures, limiting the constraints and helping everyone to see the benefits of allowing nature to do ‘its thing’?

Restricting people’s activities can actually be regarded as an investment in nature, and humanity can gain value from the benefits of quality open space rich in ecology – fresh air, clean water, mental and physical health and well-being.

As landscape architects, we need to maintain a longer-term outlook for rewilding, same as we do when it comes to plants. We need to think of the full ecosystem and not just the flora. If we want to help achieve harmony between nature and human beings, to allow for nature to recover at its own pace, to create a healthy city, the onus is on us to help get everyone to the table and make sure they are all well informed.

Footnote: Text and questions for ‘Urban Rewilding’ has been based on ‘The Rewilding’ project work by AA Landscape Urbanism 2019 graduates Deng Liu, Xian Chen, in conjunction with ©AA School of Landscape Urbanism 2018-19 and ©New Economics Foundation. All images and graphics are by the project team.