Welcome to Part 1 of a four-part interview series that delves into the project work of graduating Landscape Urbanism students from London’s Architecture Association School. [Read the Introduction for more insight]

A community approach to the deprived coastal areas in UK

The New Economics Foundation (NEF)’s initiative, a ‘Blue New Deal’, puts specific focus on the benefits to be achieved for UK coastal communities through investing time, effort and capital into understanding how to work with tourism, energy, fisheries, aquaculture and climate change as catalysts for change – importantly as a means of achieving local resilience, social well-being and economic self-sufficiency.

A small group of this year’s Landscape Urbanism graduates from AA School have taken this critically important NEF initiative and looked to how this might best be applied to Swansea Bay. An area of coastal UK that could leverage significant existing infrastructure and local natural assets to deliver much that the NEF initiative looks to achieve.

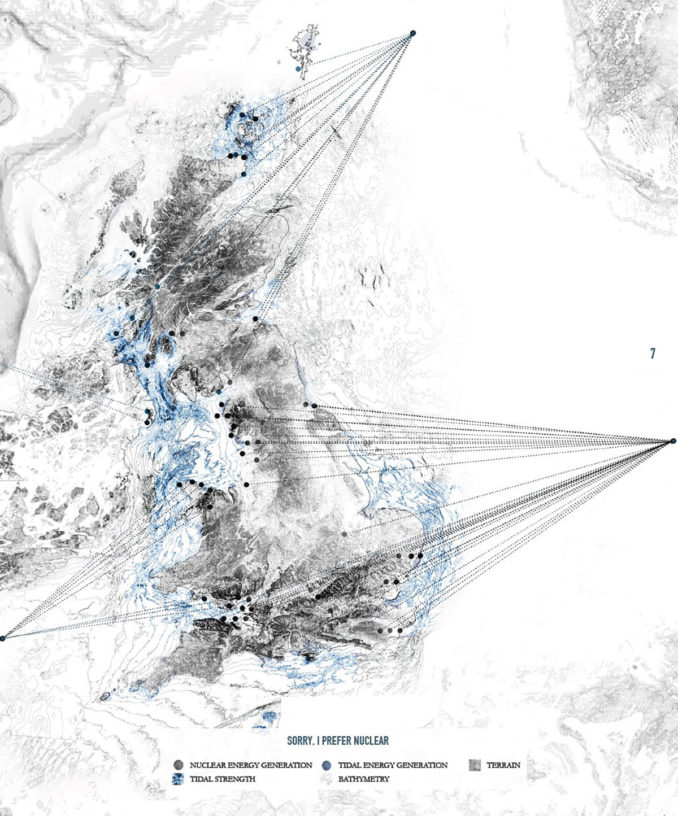

The whole of the UK west coast is rich with tidal energy potential, and if harnessed could contribute to a significant portion of the nation’s energy consumption needs – and yet tidal energy ranks as the lowest source of renewable energy in the UK. For communities living on the edge of coastal cities, in what is commonly a post-industrial landscape such as Swansea Bay, the potential here is far greater than just that of the provision of renewable energy for the wider national grid. What they have at their doorstep is both economically and socially significant, and a means of building community resilience and self- sufficiency as a region.

Swansea Bay has one of the highest tidal ranges in the UK, and, like many other coastal communities, has an existing tidal lagoon that is waiting to be re-lifed as new economic and employment driver for the town. Once a key and an essential part of the world’s largest copper industry in the 19th century, the lagoon at Swansea Bay was the safe haven for shipping and transport. It now sits idle.

The opportunity to leverage the tide as a means of generating energy for the region, both real and metaphorically, has been put forward before and is, therefore, an obvious starting point for this study. How can new energy be put into Swansea Bay and reconnect the community with the past trades, wealth and build resilience?

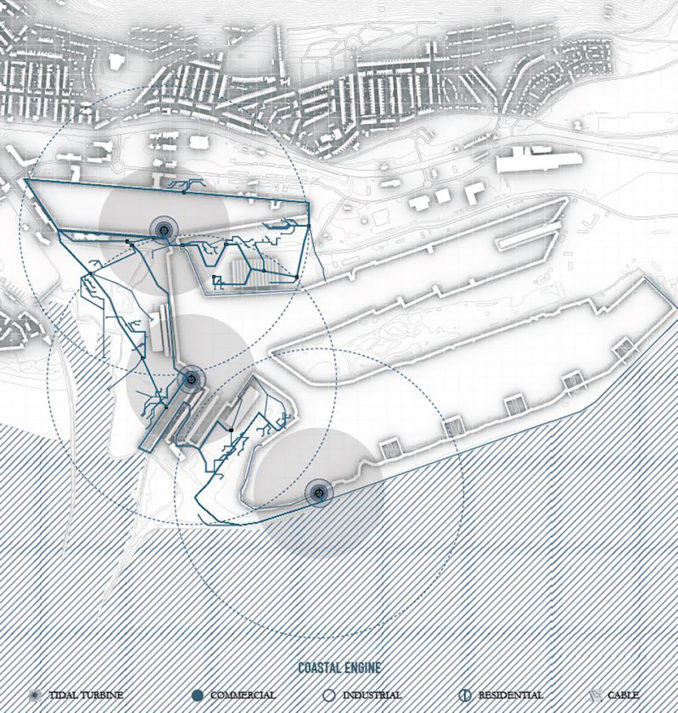

Copper was significant for the region and providing a new locally derived alterative is what the AA student group looked to define. Previous proposals have been tabled for tidal energy and have been rejected by the central government as being costly in comparison to the neighbouring Hinkley nuclear power station. But this was based on completely new tidal infrastructure to the bay and the installation of one primary energy capture point. What if though the existing maritime infrastructure was repurposed and what was abandoned after the decline of the copper industry was put back into use? What if there were more than one source of tidal energy production, and what if this concept of retro-fitting existing tidal harbour pools was repeated throughout the wider bay region? What if these power sources were linked up and working together as one single decentralised energy provider? Each town would have its own on-demand power supply – a supply that would not be drawn from the national power grid. In fact, each community with its own decentralised power supply could in fact put surplus energy INTO the grid and in turn generate an income for the townships.

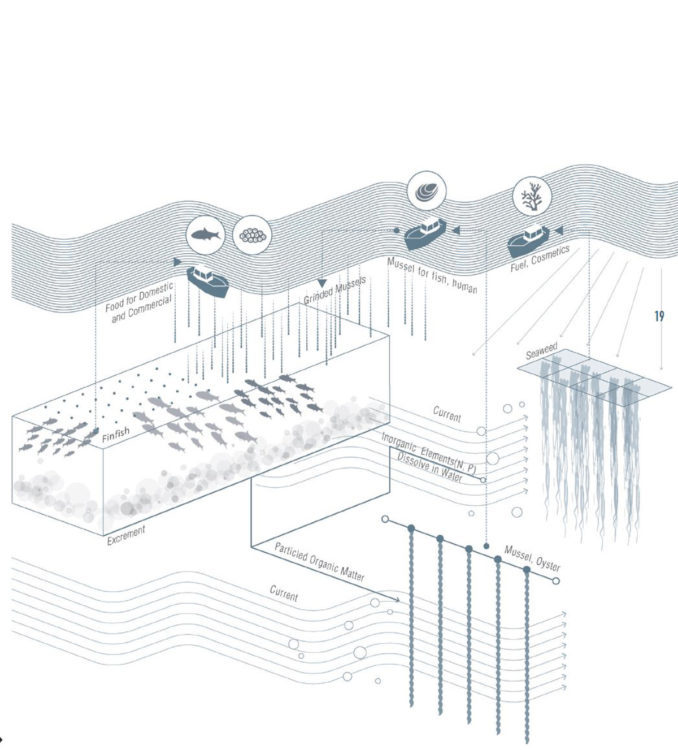

Equally, the local historic aquaculture industry has played a key role in the shape of UK coastal communities such as Swansea Bay. A revival of this trade would significantly enhance the local economy, bring employment and craftsmanship back to the region and again offer the community future resilience.

For the study group, again the tidal harbour pools offered a solution through a new coastal fisheries model that involves farming kelp and shellfish within the tidal pools themselves. Without the need for off-shore travel and transporting, and utilising the existing harbour fishery facilities, a new model could rise. Tides would assist in the flushing and replenishing of harbour waters, the aquaculture activities would enhance the environmental qualities of the bay and its ecologies – and if done well the new fisheries model could support a growing eco-tourism trade.

Interview | A discussion between the AA Landscape Urbanism Graduating Student working group and Angus Bruce (AB), HASSELL Head of Landscape Architecture

AB: Can you explain why you chose this part of the UK coast?

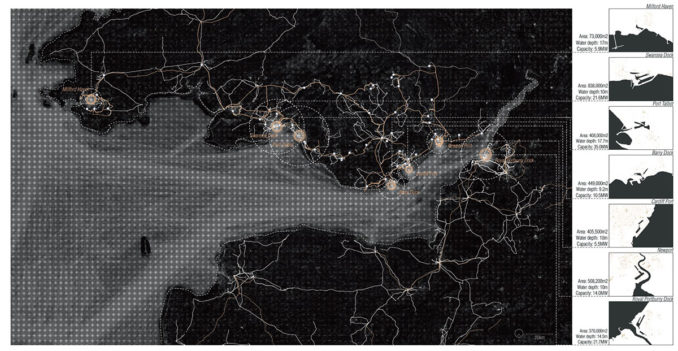

We tried to look, from an overall spatial and critical viewpoint, at the background of the current situations surrounding the coastal communities in the UK – and we mapped six (6) cartographies, that focused on the six categories from NEF Blue New Deal: tourism, energy, fisheries, aquaculture, climate change, and investment. As a result of this process, it showed that South Wales was low on all indices – lots of smaller size fishing boats, low aquaculture status, low tourist share, high erosion, and flood risk, poor energy efficiency and very little financial support.

During our research on energy potential of the UK coastal areas, we’ve found that whilst the UK has abundant tidal energy, one of the strongest tidal areas was Bristol Channel, South Wales. We could also see that there was a lot of historical land-scripts of tidal infrastructure and also many proposals to leverage the energy resource, yet none of this was actualised. Through the most recent Swansea tidal lagoon project, it was evident from the press that there was deep disappointment within the community. We were curious to dig deeper and understand why there didn’t seem to be any traction.

AB: How much direct community consultation did you undertake and do you think the locals will be receptive to your proposal?

We spent a great deal of time on site, meeting and talking with locals, and helping to underpin our research. We met with community groups, tidal technical specialist, local council officers (not officially), and sediment experts.

Whilst our proposal doesn’t generate the same scale of electricity output as the previous proposal, it equally is not of the same cost magnitude. Being locally based and decentralised, is a unique advantage over the previous private investment company proposal. The electricity generated through our smaller proposition would allow for battery storage in existing buildings within the local community and would be managed by the locals to sell as surplus to the national grid as locally derived income.

AB: What was behind the previous tidal energy proposal not getting real traction?

We want to respond to this one very carefully, but from our research we believe it came down to:

- Political attitudes/stances towards renewable energy.

- Cost of the community based renewable energy infrastructure compared to that of private investment nuclear power, without valuing what the proposal would have achieved for the community and the planet as a whole

- Environmental approvals

- Sheer scale of the proposal, which wasn’t leveraging existing infrastructure, but instead building new

AB: Who owns the tidal pool infrastructure and therefore who has the real trump card here in making this happen?

This tidal pool infrastructure owned by Associated British Ports. Currently, they own and operate 21 ports in the United Kingdom and Swansea dock is just one.

AB: There are numerous similar townships along the UK coastline that have similar local issues that a project such as this would help address and the same potential when it comes to utilising the natural tides. Do you believe this can be repeated elsewhere?

The original Swansea Bay tidal lagoon project was a pilot exercise to test the feasibility of the idea, with the intent being to apply it to five other tidal lagoons as a series of connected projects. Nominally this concept is highly applicable to Cardiff, Newport, Colwyn Bay, West Cumbria, and Bridgwater Bay.

AB: Is there an upside to the critical mass that would come from a series of similar projects working together but decentralised and off the national grid?

The proposed community-based energy system offers an alternative to Swansea that would be a cheaper and cleaner energy source than is currently available. The economic benefit of this energy production linked up between communities would aid in locally driven business growth, tourism and aquaculture.

AB: Aside from the idea of tidal energy, your work proposes a new form of aquaculture, which would reengage the community with the past coastal activities. What are some of the examples of the products that kelp contributes to and which of these would you see as most relevant to this area of the UK?

The aquaculture industry, as well as copper, was a very popular business sector in Swansea, especially in the Laverbread industries. Historically “Welsh Laverbread” was very important as a nutritious high energy food source particularly for hard-working pit workers in the South Wales mining valleys where it became a staple breakfast food. Women and children, who also worked underground in the pits were often malnourished and were advised by doctors to eat Welsh Laverbread because it was a very good source of iron.

In 1800-1950 collecting laver to make “Welsh Laverbread” was a small cottage industry. The laver was thrown over thatched huts to dry before being picked up by a horse and cart and taken to Pembroke station to be sold to businesses in Swansea where it was cooked into “Welsh Laverbread” and sold at local markets. Although laver was historically sourced on the Pembrokeshire and Gower coastline it is now mainly collected along the coastlines of North and South Wales, but still brought to Penclawdd in Gower to be processed.

Laverbread is a well-known Welsh delicacy recognised both within and outside Wales. It is an acquired taste, traditionally eaten fried either as it is or rolled in oatmeal and usually eaten with bacon and cockles as a traditional cooked Welsh breakfast.

The more globally recognised product though is ‘Nori’ meaning seaweed snack. Nowadays, this is a highly popular snack in the UK and as a dry-product it has a high market value than the wet value

….and then there is the cosmetics industry where the likes of SeaKelp products exists through UK business such as The Scottish Fine Soaps Company.

AB: Where do you see yourselves next year, now that you have graduated?

We would each like to take our studies and apply them into projects that benefit communities. One of us wants to take on a Ph.D on coastal communities and the rest of us are eagerly looking for work as landscape architects and getting our ‘hands dirty’.

Footnote: Text and questions for ‘New Coastal Economies’ has been based on the “Swansea ‘New Deal’ project work by AA Landscape Urbanism 2019 graduates Eunji Lee, Minxiang Huang, Jianxin Liang, in conjunction with the ©AA School of Landscape Urbanism 2018-19 and ©New Economics Foundation. All images and graphics are by the project team.