As part of World Landscape Architecture Month we are featuring landscape architects from around the world. We had the opportunity to speak with Frederick R. Bonci about why he became a landscape architect and the future of landscape architecture.

Frederick Bonci is a founding partner of LBA Landscape Architecture, established 40 years ago. He has been the leader of many of the firm’s community planning, urban design, public open space, and sustainable design projects. His knowledge and extensive experience with urban projects have led to an ever-increasing number of commissions, locally in the Pittsburgh region, nationally, and internationally. The majority of these projects focus on the creation of socially engaging public open spaces that create viable, healthy, livable, and sustainable places. Some of his most notable commissions include Pack Square Park in Asheville, NC, Summers Corner in Summersville, SC, The Frick Environmental Center, a certified Living Building, in Pittsburgh, PA, the Westmoreland Museum of American Art Expansion and Gardens, LEED Gold certified, in Greensburg, PA, University of Pittsburgh Central Campus Public Space Initiative, and over 20 Hope VI neighborhoods. He is currently working on the eco-campus for the Carnegie Science Center and Allegheny Shores, a new 50-acre mixed-use riverfront community on the Allegheny River in Pittsburgh.

WLA: Why did you become a landscape architect?

Like many landscape architects, accidentally. My childhood influences were my uncle, who was a design/build contractor, and my grandfathers, who were stone and brick masons. As a child, they took me to their work sites where I became fascinated with design and the craft of building. I grew up in a small town with unlimited access to farms and natural amenities within biking and walking distance of my home. Between my freshman and sophomore years at The Pennsylvania State University, I worked my first summer job for a railroad company. I carpooled with another person from my hometown who always had books related to design, architecture, landscape, and nature. When I asked him what he was majoring in, he said Landscape Architecture. It seemed to be a perfect fit for me. As they say, the rest is history.

WLA: How do you start the design process?

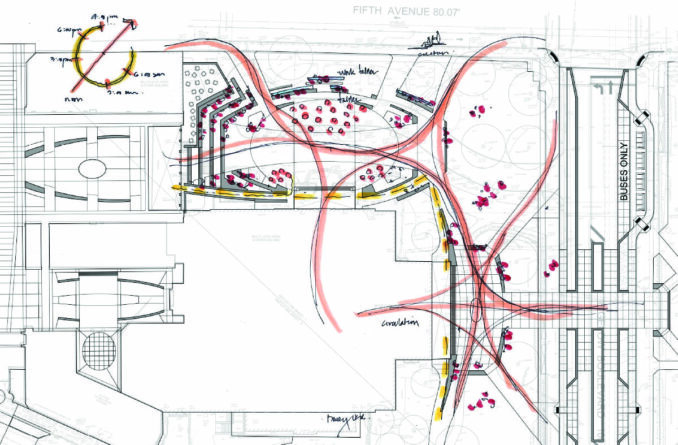

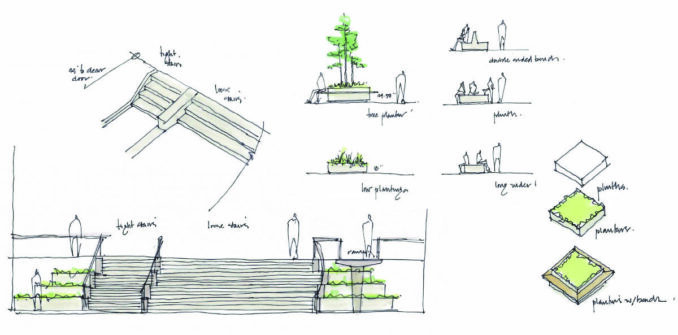

I was mentored by some fabulous landscape architects. My first job experience was with Edward D. Stone Associates (EDSA) and while there I learned three valuable lessons that shaped my career – compile a diverse knowledge base to truly understand your fellow professionals so that you can lead them collaboratively; never stop challenging your clients and colleagues to strive for better solutions; and to simply be the first to pull out a piece of trace paper and begin to draw. When you draw something, the dialogue becomes richer and more vibrant, and the conversation begins to focus on the possibilities and not the constraints. In mentoring my colleagues and associates, I stress two things – we are never done educating the public and our clients and we are never done learning.

WLA: How do you see the future of landscape architecture?

As a global society, we are divided and conflicted about many key issues – political polarization, climate change, and social equity issues. This impacts our profession dramatically. At LBA, we design towns, neighborhoods, environments, and public spaces. We strive for the highest level of ecological diversity and sustainability in our projects. We engage our clients and the people we are designing for in our projects.

Engaging people in the design process is more important than ever. We start our conversations by asking people to recall their most memorable moments and experiences about community. We ask them what they long for, what they are missing, and what they need. We ask them to dream. To that end, in all walks of life and economic situations, we find that they all come to the same place.

We no longer mention climate change. Instead, we discuss how to stay cool and how to solve flooding by integrating stormwater into our designs.

We no longer mention traditional town planning or the fifteen-minute city. Instead, we present ideas that solve accessibility and celebrate community.

We no longer mention inequity. Instead, we present ideas about creating democratic spaces for all.

We need to become bolder about finding ways to enrich the dialogue and take a more enhanced leadership role in design.

Thank you to Fredrick for taking the time to answer WLA’s questions.