Authors:

Tim Church, Partner | Urban Designer, Boffa Miskell

Stephanie Griffiths | Urban Designer, Boffa Miskell

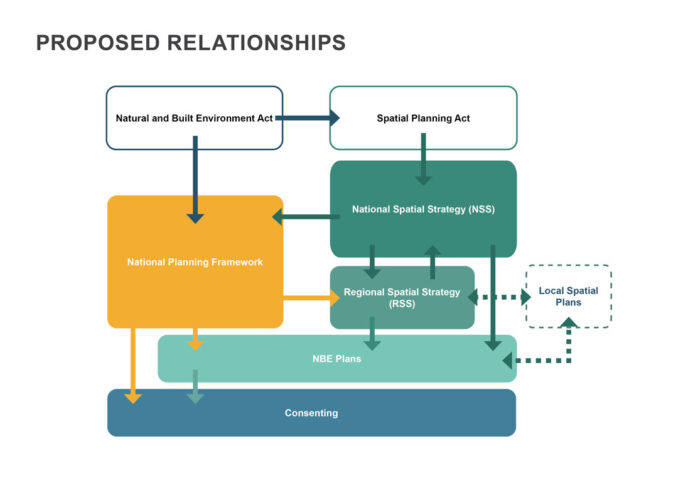

New Zealand’s (Aotearoa) resource management system is undergoing the most significant review since the Resource Management Act (RMA) was enacted in 1991. A key outcome is the proposed Spatial Planning Act (SPA), alongside the Natural and Built Environments Act (NBA) and Climate Adaptation Act (CAA).

The SPA will require the preparation of Regional Spatial Strategies (RSS), mandating regional spatial plans to comprehensively address issues of regional importance: area protection, restoration or enhancement; cultural heritage and resources; land use and transport integration; infrastructure provision; appropriate use of rural and coastal marine areas; and managing natural hazards and climate change.

Whilst spatial planning requirements at the regional level are becoming clearer, key questions have emerged: will they be strategic enough to effectively coordinate and address issues of national importance? If not, do we need a National Spatial Plan (NSP); and if so, what would it entail?

What is a Spatial Plan?

A spatial plan is a high-level, future-focused strategy outlining a comprehensive plan and rationale for an area’s development and transformation over three decades. A shared inter-generational vision establishes clear expectations for managing environmental change and various interrelationships and dependencies. Spatial plans set the scene for liveable, well-functioning urban environments within a broader environmental, economic and social context. They integrate various plans, strategies, and projects to achieve sustainable outcomes.

Central Government and Local Authorities are increasingly utilising spatial planning as a proactive approach to managing change, aiming to comprehensively tackle challenges up-front.

The Challenges

During the Bill’s progress through Parliament, the proposed SPA garnered industry support from organisations like NZPI and UDF Aotearoa. However, these groups identified a crucial missing component – a National Spatial Strategy incorporating a National Spatial Plan.

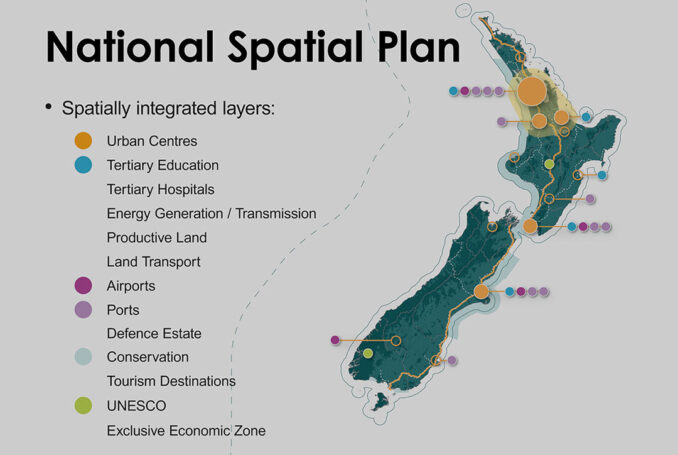

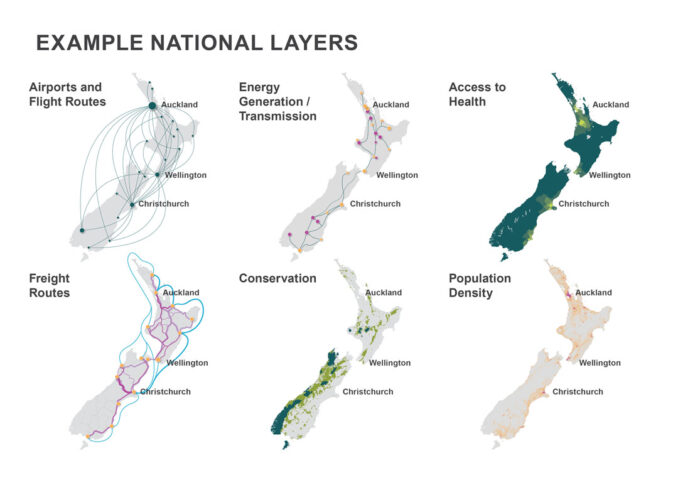

Without a National Spatial Plan, we cannot strategically respond to the over 1,900 international treaties New Zealand has committed to, covering environmental, social, cultural, and economic matters. For example, COP15 aims to reverse the destruction of nature by 2030 and protect 30% of the planet’s land and sea. Approximately 30% of New Zealand’s natural areas are protected, predominately under Department of Conservation management. But within our 12 nautical mile limit, only 7% of our seas are protected. Without a National Spatial Plan, it seems unlikely to strategically address the remaining 23% of the sea and harness the potential mutual benefits of other land and coastal marine uses, such as tourism, renewable energy and food production.

The need for an NSP is increasingly urgent due to the mounting complexities in urban and regional planning. The New Zealand Infrastructure Strategy estimates that over the next three decades, the population could increase by 1.7 million people [1]. Additionally, the global impacts of climate change pose nationwide risks, requiring proactive measures to mitigate and adapt to its effects. While provisions have been made in the SPA to consider cross-regional issues, these are unlikely to comprehensively address such existential challenges. The NZPI has identified the risk that a de facto national spatial strategy may emerge solely from collecting individual RSSs, lacking alignment and national oversight [2].

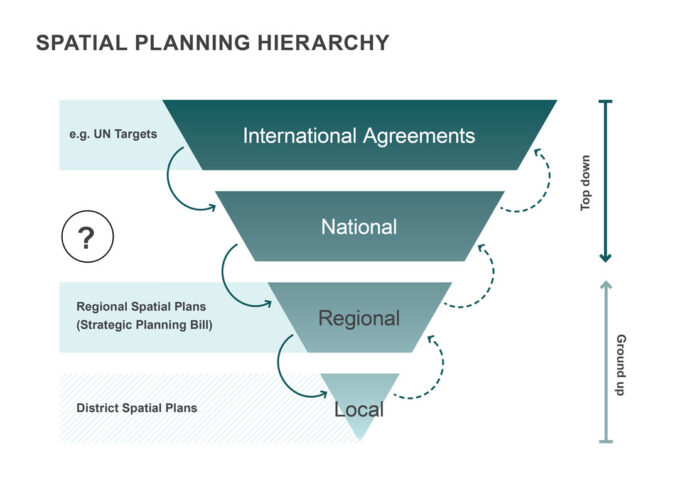

Implementing a National Spatial Plan is not without challenges. While an NSP provides a broad vision, engaging with local communities and empowering them to participate in decision-making is crucial, ensuring that the plan supports their unique aspirations, values and needs. While Te Tiriti o Waitangi is central to commitments and shared responsibilities between the Crown and Tangata Whenua at a national level, local partnerships with iwi, hapu and marae or Mana Whenua will shape responses at a local level. Importantly, we see the NSP as being part of a hierarchy of spatial plans (Figure 1), with each fulfilling a specific role between top-down and ground-up initiatives.

A National Spatial Plan can support global competitiveness though a strategic alignment of infrastructure and resources. For example, strategically locating universities, research centres, and training institutions in close proximity to thriving industries and innovation hubs enhances New Zealand’s appeal as a destination for global talent; attracting investments, fostering innovation, and driving sustainable economic growth in an increasingly interconnected and competitive global context.

An NSP opens significant opportunities for creation and management of national databases and tools. Centralising consistent and reliable spatial data and information at a national level ensures a common foundation for analysis and decision-making at subsequent scales. This unified approach fosters transparency and reduces duplication of efforts. Additionally, the establishment of consistent methodologies around measuring change enhances the accuracy and reliability of projections related to population dynamics and infrastructure demands. Consistent assumptions serve as a crucial basis for long-term planning, enabling policymakers to make informed decisions and allocate resources efficiently, resulting in sustainable and well-managed growth across the country.

As UDF Aotearoa states in their submission, a National Spatial Plan is not a new concept. Several countries, including Denmark, Wales, Ireland and South Africa, have already embraced this as an effective strategy [4]. New Zealand’s isolation, manageable size and modest population presents a unique opportunity.

Several national agencies and strategies are already in place, such as the New Zealand Infrastructure Strategy and various National Policy Statements. Although these existing frameworks may not be spatially focused, they can serve as a solid foundation that can be transformed and integrated into a comprehensive NSP.

With ongoing changes in the planning system and the upcoming creation of the National Planning Framework (NPF), there is a window of opportunity to incorporate spatial planning at the national level. By acting now, we can create a National Spatial Plan that the RSSs could give effect to and ensure a coordinated and aligned approach across all regions.

The Opportunity

We consider Local Authorities tasked with preparing Regional Spatial Strategies under the Spatial Planning Act to benefit considerably from a National Spatial Strategy and Plan to address national (and international) issues and achieve effective integration between regions.

This would complement the National Planning Framework already provided for in the Natural and Built Environment Act and numerous other national-level strategies that currently lack comprehensive mapping and integration. With our resource management system undergoing a significant review, it is a timely opportunity for Central Government to add one last missing piece to complete the puzzle.

Like the National Planning Framework, we can take it one step at a time, initially gathering what we know and then progressively joining the dots from there.

The inclusion of a ‘top-down’ National Spatial Plan fills an important gap in our spatial hierarchy, providing a more cohesive and strategic approach to mid-tier, Regional Spatial Strategies, supported by ‘ground-up’ local spatial plans that are already underway by many Local Authorities.

Better alignment between national and local initiatives will facilitate effective decision-making, improved resource allocation, and enhanced collaboration to support New Zealand in a highly dynamic and competitive global context. Countries much larger than our ‘team of five million’ are doing it, so why not us? To harness this opportunity, we urge Local Authorities, along with their iwi and industry partners, to advocate to Central Government to prepare a National Spatial Plan.

Does Aotearoa need a National Spatial Plan?

Authors

Tim Church, Partner | Urban Designer, Boffa Miskell

Stephanie Griffiths | Urban Designer, Boffa Miskell

References

[1] Rautaki Hanganga o Aotearoa 2022 – 2052 (New Zealand Infrastructure Strategy), New Zealand Infrastructure Commission

[2] Submission on Natural and Built Environment Bill and Spatial Planning Bill, New Zealand Planning Institute

[3] Submission on Natural and Built Environment Bill and Spatial Planning Bill, New Zealand Planning Institute

[4] Submission on Spatial Planning Bill, Urban Design Forum (UDF) Aotearoa