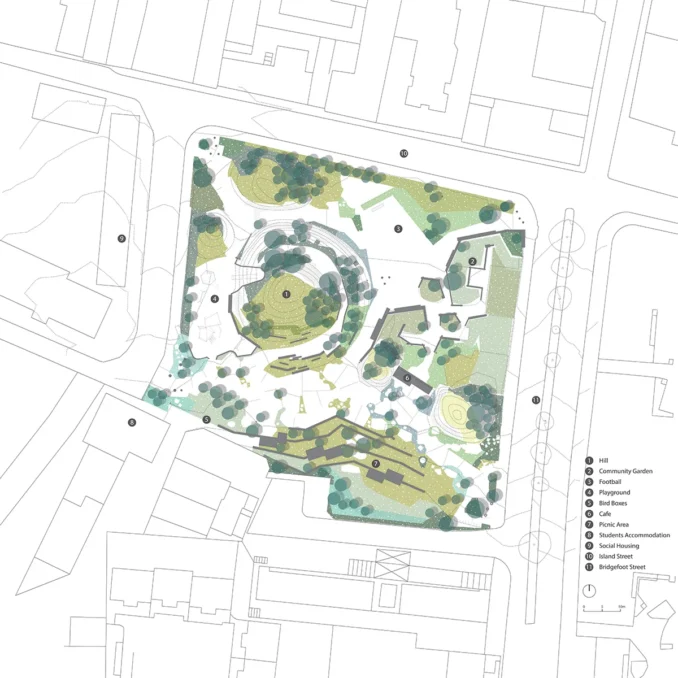

Bridgefoot Street Park is a unique spatial composition, which uses construction and demolition waste, in the form of secondary raw materials, to create Ireland’s first such permanent public space. The new one-hectare park in Dublin’s city centre addresses global environmental challenges in a synthesized and beautiful way, laying the foundation for aesthetic and even legislative change in Ireland. Over 2,000m³ of what would have been waste were creatively redirected away from landfill, the embodied energy now permanently contained within the park.

An artistic expression of the environmental sciences

The hallmark of this project is the way in which a new aesthetic, as it arises from partially predictable natural processes, is presented to the public. An understanding of the science of emergent habitat on waste materials helped us to implement the project, but the outcome is the artistic expression, more so than the science. The phraseology of the artistic outcome comprises several components: a lexicon – incongruous geometries and composition, form(s) that represent a particular aesthetic of waste (broken, chipped, fragmented, cracked), emergent volumes of seasonal texture and colour, topography of waste, wildness.

People dwell in this space not despite its wild eccentricity, but because of it. Its ‘natural intelligence’ emerges through the entanglement of ecological systems and cultural practices: collective actions of a community garden, public consultations demanding ‘nature,’ local researchers tracking ecological rhythms. Here, food plants entwine with wild ruderal species; bees colonise dry banks; children play on hills made of salvaged concrete as boulders – all underpinned by unseen ecological and social wisdoms.

Building the park

Realising this required inventive design methods. It involved physical and didactic trials: doctoral research into the artistic qualities of waste, a range of sketching and diagramming, the production of a non-pricing document, and the construction of a trial garden, alongside technical specifications ensuring contractors grasped the ethos without distorting standard procurement processes. Ultimately, this led to designer, contractor and user consciously and unconsciously creating the conditions for species to reawaken from the seedbank (poppies), arrive by air (thistles), or slip in unnoticed (gazanias), Trojan-like, carried by soil and time.

The ‘technological’ side of constructing the park is ancient, simply collecting materials that nobody wanted and then creatively processing and re-using those materials. The research into the method was done in several locations before the practice was commissioned to design the park. With Bridgefoot, we were able to implement some techniques in a permanent configuration which is open 24/7.

Secondary raw materials were employed to make novel landscape finishes, new topography and sub-bases, including paving, retaining elements, loose aggregate and aggregate for in-situ concrete. Small quantities of calp stone and brick ‘seconds’ (waste from the manufacturing process) were also used as paving. Recycled glass and brick ‘seconds’ were used for in-situ concrete.

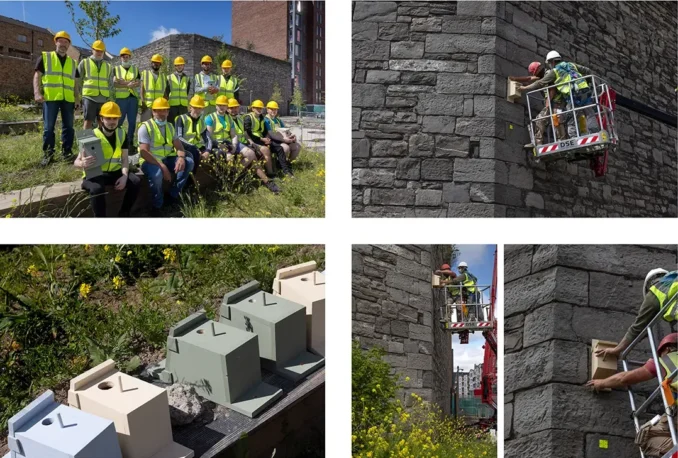

A sample garden was designed and constructed before the contractors were invited to tender competitively for the contract to build the park. It was left in place for one year so that we could see what emerged on the site. It was also used to demonstrate the potential of reusing waste to administrators and to help contractors to understand what kind of construction project they were competing for. The garden functioned as an outdoor research laboratory with many useful outcomes, in terms of aesthetics, process, methodology and pricing. It gave everyone involved the confidence to go ahead and make the investment in the park.

Social impact and engagement

The project involved the rezoning of land for much needed public open space in a neighbourhood that includes a complex demographic but suffers from unemployment, substance abuse and other social problems. From the start, we engaged creatively with a range of people from the surrounding community, sharing knowledge with gardeners, commissioning bird boxes from early school leaver trainees and facilitating the installation of a sculpture by members of a prison after-care service aimed at rehabilitation.

The park is not simply made of waste, but also maintained by low-level gardening interventions: grubbing, turning, disturbing the soil to awaken buried seedbanks and release waves of spontaneous germination. What might elsewhere be erased by herbicide here flourishes into full view, its unruly beauty challenging standard horticultural control.

The park addresses climate resilience in a synthesised and beautiful way, laying the foundation for aesthetic and even legislative change in Ireland and at the same time creates a space for people to engage with the ‘natural’ world right on their doorstep, in a neighbourhood with a very low public open space metric.

Bridgefoot Street Park

Location: Dublin, Ireland

Landscape Architect: DFLA

Client: Dublin City Council

Collaborators/Other Consultants:

Civil Structural Engineers: Horgan lynch Consulting Engineers

Mechanical engineers: IN2 Engineering

Main contractor: Bracegrade

Photographer/Image Credits: Gareth Byrne, Paul Tierney