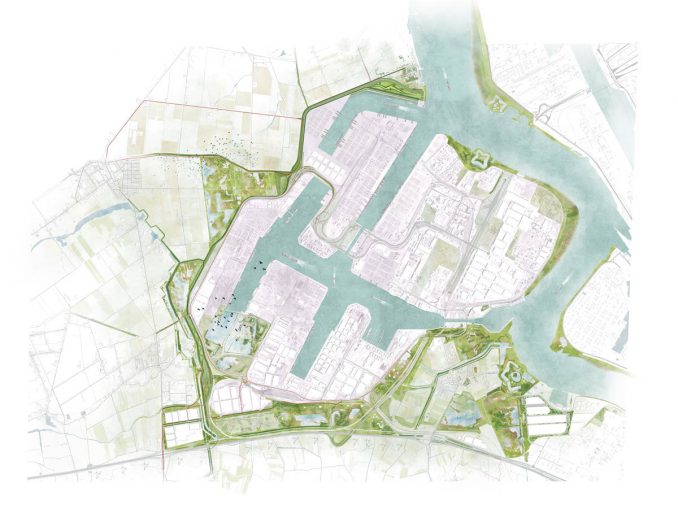

In 1960 a thriving polder village of 1500 inhabitants Doel became a ghost town with only 8 people left today. A big container dock for the second biggest harbour in Europe, Antwerp, had to be built in the village. Action groups in return succeeded several times to halt the construction of the dock. This decades-long battle created a lot of uncertainty around the future of the village. Now it seems that after more than 60 years a solution is found to save both the village and the dock, partially thanks to the landscape.

The dark future brightened up for the first time in 2019 due to the Scheldt river. Sedimentation models showed that the planned dock was not ideally located. The position of the dock had to be adjusted and was moved next to the village. It looked like the conflict between the government and action groups just found a common ground. The village and the dock could stay, but livability questions became an issue – isn’t it too loud living next to an enormous 24/7 harbour with sea vessels passing by and millions of containers being loaded? The port authorities weren’t so sure.

The future of Doel and the dock became dependent on a small strip of land between the village and the harbour. A big design question arose. How does this landscape have to function to create a livable village?

In reaction, the Flemish Government, Port of Antwerp-Bruges and MLSO initiated an ambitious landscape study that has to mitigate noise, light and visual pollution not only for the village of Doel but for the natural areas and other settlements around the harbour. A team of landscape urbanists of OMGEVING, livability experts and action groups designed in cocreation an 11-kilometres-long buffer landscape that aims to become a destination for nature, recreation, green mobility and energy production. It will become the new face of the harbour.

The high ambitions of this narrow strip of land create a lot of design challenges. The demand for high dykes on unstable peat soils, that act like building on pudding, led to the development of three new dyke typologies.

- The full dyke has the most space and resembles a normal dyke but is remarkably higher, up to 24m. At the harbour side, awaiting an energy study, the slope is cladded with solar panels, and the polder side is made accessible to hikers, wheelchairs, mountain bikers, horseriders, and functional and recreational bikers. [Figure 1]

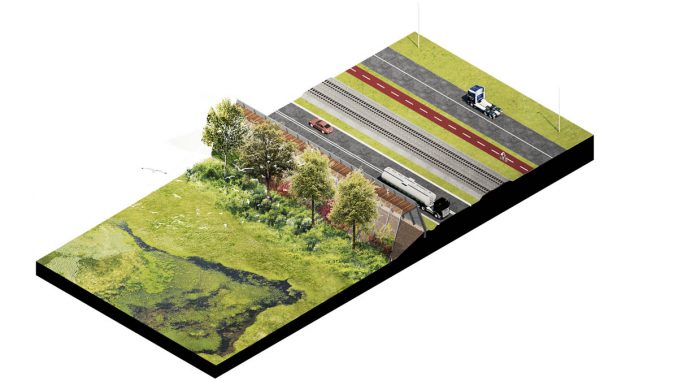

- Where space is lacking severely a hollow dyke is proposed. The modular construction of two 70° angled panels reaches up to 14m in height. The harbour side is cladded with noise-reducing solar panels and the polder side will be covered by climbing plants. In this nature inclusive mesh, openings are made to nest birds and bats. On top of the dyke looking over the nature, that had to be compensated for the harbour expansion, a walking path is installed. Making this one of the largest bird-watching walls in Europe. This light-weighted construction is necessary as the fable peat soils can’t be pressured too much. [Figure 2]

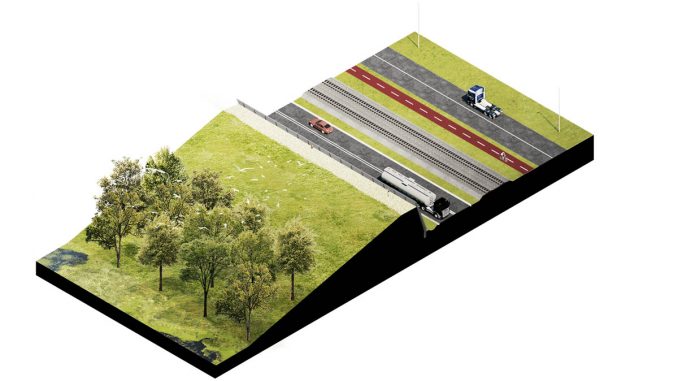

- The third variant works using a mix between a full and hollow dyke – the half dyke. The polder side is executed as a natural slope and the harbour side consists of a 70o noise barrier with solar panels. [Figure 3]

A continuous line of 20m high poplar trees at the bottom of the dyke filters the light and visual pollution of the harbour even more and makes the dykes blend into the polder landscape. The water of the dykes and roads is infiltrated in ditches at the bottom of the dyke providing water for the wetlands below.

The sand used for the dykes will be dug out of the newly constructed dock, thus reducing transport CO2 emissions. Two areas will be heightened severely. One creating a polder hill of 40m high which will become a new landmark in the older.

The other one, the head of Doel, is designed as a 24m high and 150m wide inverted dyke. A canyon will be dug out of the crown of the dyke to create a nature sensitive play landscape. Due to this introverted topography, there is no disturbance to the skyline. A flat dyke will be seen from the polder. The inverted landscape will create space for a professional mountain bike park and a play landscape that depicts the finding of a medieval ship found by digging out a nearby dock. At the polder side an exercise zone for paragliders can be created, while horse riders, bikers and hikers can enjoy the breathtaking views on top of the dyke over the village of Doel and the arriving sea vessels.

Dykes have always given expression to this flat landscape. Since the 10th century AC settlers have tried to conquer land on the sea by building higher and better dykes. By reinventing the typology of the dyke we build further on this identity. The dykes are a moderator to bring peace to the conflict between villagers and port authorities. Just as the dykes brought peace between settlers and the sea in the centuries before.

But what now with the village of Doel?

The village of Doel is saved and can slowly rediscover its role within this altered landscape. Therefore, OMGEVING and RE-ST architects led a study, initiated by the Flemish Government, finding a new reason for an existence based on the new landscape qualities.

- First of all, we tried to find a connection with the Scheldt river. What could the nautical future of the village look like?

- Next, we unearthed the polder landscape. What forms of nature inclusive agriculture can be introduced in the village?

- Thirdly, we rediscovered the historic village landscape and the remaining buildings and gardens. What could be the new program for these places?

- Lastly, we found a connection with the harbour landscape. Attaching the future of Doel to this 11km long recreational buffer landscape. Which touristic revenue can be found in this landscape to restart the village?

As Doel existed in the 17th century due to farming the fertile polder land, it will have to find a new way of ‘farming’ the altered landscapes around itself. Only this will create a durable and slow growth for the village.

The mediating role of the landscape was written by Landscape Urbanists Sven Augusteyns and Paulius Usevičius of landscape architecture firm OMGEVING. Images courtesy of OMGEVING.