Dryfo Urbanism transforms the sprawling patchwork of informal settlement in Cartagena, Colombia for an organized system where the landscape is the protagonist. Instead of imposing the modernist visions of individuals or isolated social housing projects over the expansion zone of the city, this proposal reveals both the voice of the territory and its inhabitants. The lines of existing vegetation of the grazing land once used to separate lots and people are leveraged as the departure point of urbanization. Coupled with this structure is a systematic planting of the dry forest to not only reserve future mobility corridors but establish a sense of pride and appropriation with an undervalued ecosystem. This proposal imagines a future Cartagena where the dry forest is treasured and celebrated as the main component of communal interaction and collective memory.

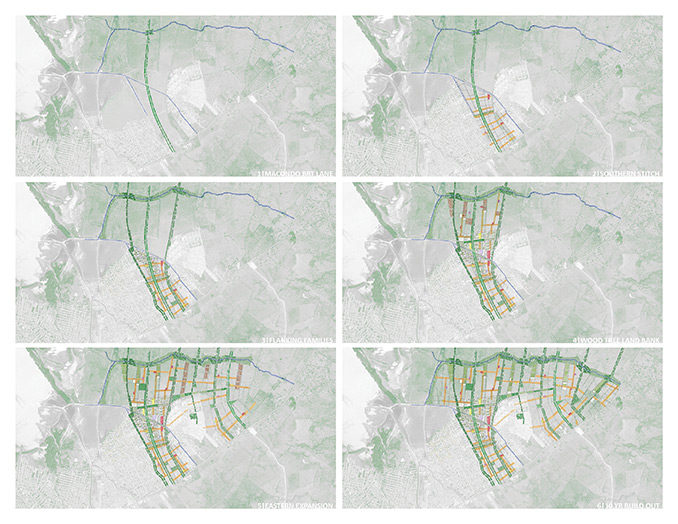

Cartagena has suffered from a great deal of short-sightedness. Focused solely on its economic engine of the historic city of El Centro and its beaches, the investment of the city have blatantly ignored the harsh realities of a city that is composed of 70% informal settlements. Combining the displacement of a city facing alarming sea level projections and a steady population growth rate of 1.2%, Cartagena will eventually have to accommodate a population that will double in a span of only 30 years. Although current plans designate the grazing land of the eastern part of the Ciénega De La Virgen as the urban expansion zone, there are no rules, codes or timetables for such implementation. Dryfo Urbanism proposes to structure the territory through a leveraging of the existing vegetation, interweaving an orchestrated planting of the dry forest providing the framework for informal and formal infill. Projecting a future where the landscape is an integral part of the public realm, this proposal establishes the grounds for citizens to enjoy the benefits of shade and undeniable beauty.

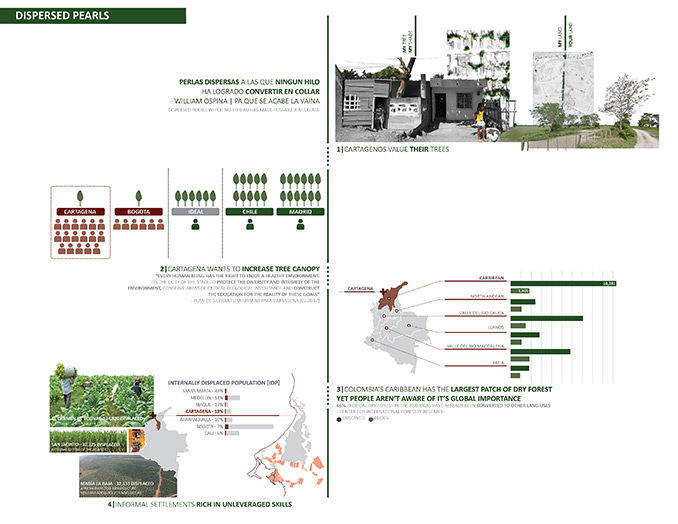

Reflecting on a historically fragmented nation, contemporary Colombian writer William Ospina defines it as “dispersed pearls which no thread has managed to transform into a necklace.” From decades of casting aside the indigenous people and polarizing mountainous and coastal citizens, Colombia has yet to achieve a self-acknowledgement of what it means to be the second most biodiverse country in the world. Biodiversity does not consist of just flora and fauna but encompasses both nature and the plethora of culture enriching it.

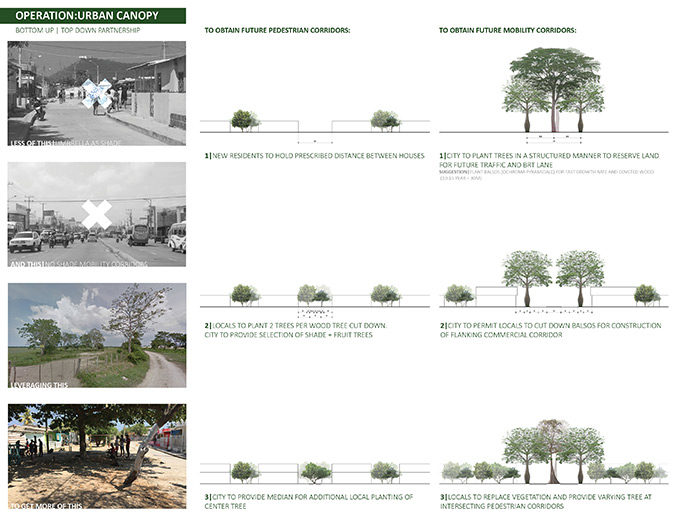

Cartagena shares the repetitive trend of Colombian fragmentation. Seeking the dispersed pearls of the city itself, we can identify four elements crying for a larger agenda and vision. To start, people in Cartagena value their trees as most informal housing develops from the backyard to the street with the first element being a tree. This simple act shows a valorization of shade in the hot Caribbean climate. Roaming around Google Earth, one can quickly identify the vegetation between houses with stark contrast with the streets where barely any is present. Without any governmental assistance, what gets prized in individual households is never translated into the public realm.

Adding to this local scale initiative is governmental desire to increase the tree canopy. In February of 2017, The Urban Forestry Plan for the City of Cartagena published a plan identifying the lack of trees with a ratio of only 1 tree per 17 people. These statistics fall significantly short of the recommended range of 4-6 trees per person. To obtain even a basic 1 to 1 ratio, a daunting 16 trees would have to be planted per person without accounting for current population projections.

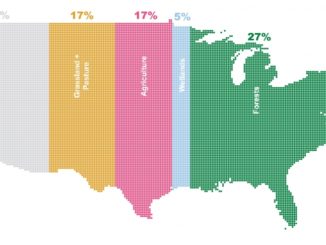

A third pearl evident in the city of Cartagena is the predominant presence of the dry forest. As an ecosystem that has already suffered a 66% conversion into other land uses throughout the Americas, Cartagena can respond differently to the same threats and challenges. With proper education on its global value and beauty, Cartagena could reverse the trend of its traditional depletion through integrating the dry forest into the daily lives of its citizens.

In its final pearl, Cartagena must learn to recognize its diversity of people. Already a nation with the world’s 2nd highest population of internally displaced persons, (IDP) Cartagena ranks 5th in displaced population, creating severe socio-economic conflicts between citizens. Instead of seeing one another as equals and Colombians striving for progress, segregation, competition, and even homicide plague these communities. If Cartagena could learn to value its displaced population digging deeper into their origins, they’d find that they come with skills not readily accessible in urban contexts which could be shared and leveraged as a single collective. Considering only the cities of the Bolivar department with high migration patterns, displaced people can have skills ranging from agriculture, forestry and even artisanal craftwork. Providing the space for these skills and wealth of knowledge to be shared, one could truly direct social impact projects.

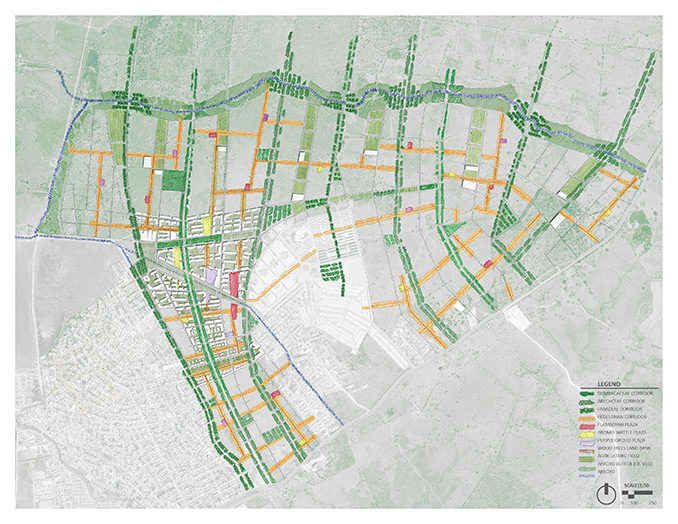

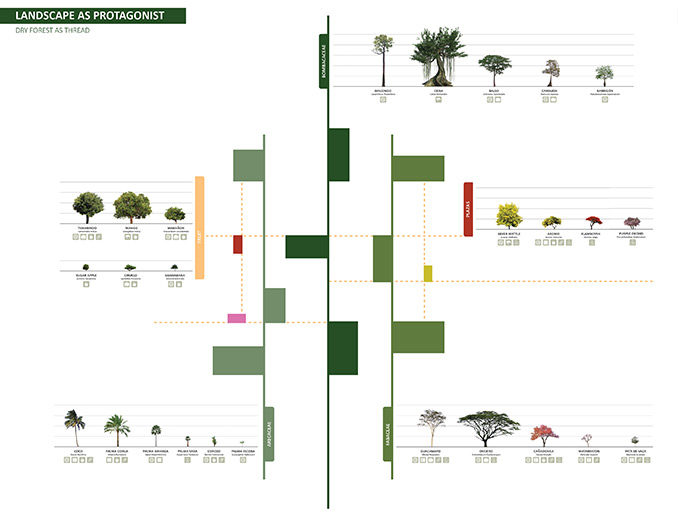

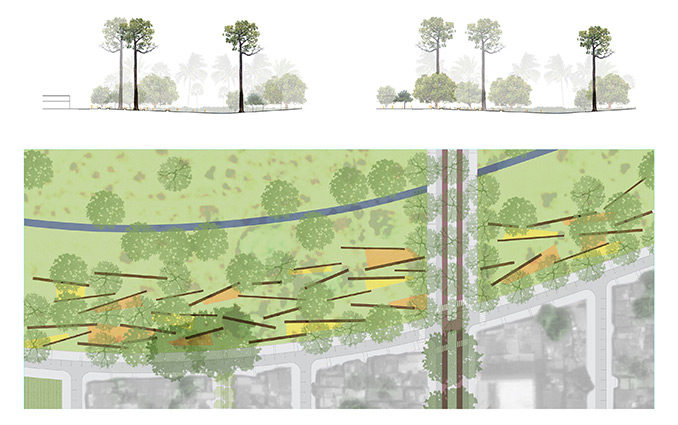

Dryfo Urbanism proposes to make of these dispersed pearls a necklace by placing the dry forest as the protagonist of future development. A selection of three families is used to strengthen and extend the existing lines of vegetation from the grazing territory. The Bombacaceae family is chosen to instil a sense of grandeur and pride in citizens through the sheer monumentality of its trees. The Arecaceae family is planted for its range of palm trees with varying leaf structure creating elaborate shadows and patterns. Finally, the Fabaceae family is featured for its status as the largest family of the dry forest, displaying its wide range of color and textures.

Flanking each corridor could be a series of plazas acting as dense islands of each family. With a diminishing degree of design and control approaching the arroyos and bodies of water, the evolution of these spaces could integrate government and local needs and skill sets. To reserve the land for these amenities, the government could work with local leaders to plant wood trees as a land bank system, chopping them down for future construction and furniture material as the city expands. Replacing these patches could be network community centers, schools and agricultural fields generating urban nodes while serving as stewards over these invaluable assets of plazas and parks.

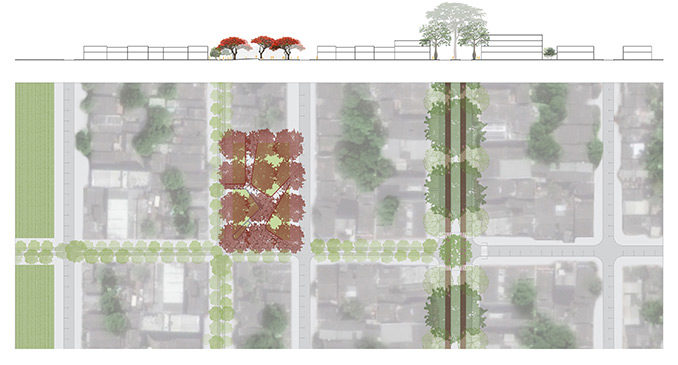

With the necessary North-South corridors established, the dry forest families could be threaded together by a selection of shade and fruit trees providing pedestrian corridors with invaluable shade. Intersecting pedestrian streets could have small pocket plazas highlighting a distinct color of the Fabaceae family. Instead of honoring individuals and conquistadores such as Simon Bolivar, these plazas could be named after the tree itself instilling a botanically educated city where local appropriation and sense of place is generated through the humble planting of trees.

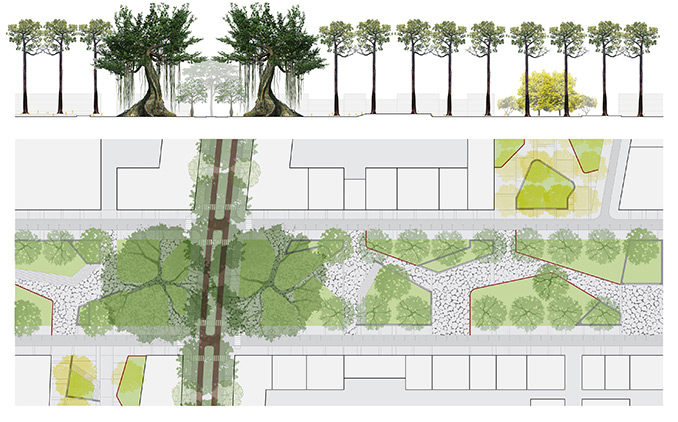

To achieve a higher degree of resolution on the character of the corridors, the Bombacaceae family is selected for the cultural association of the Macondo tree. Globally recognized as Colombia’s most distinguished author, Gabriel Garcia Marquez named Macondo the location of his fictional city in the infamous 100 Years of Solitude. Unfortunately, without the knowledge that Macondo was a tree, the tree has since become inevitably tied to solitude. Dryfo Urbanism hopes to reverse this reality by featuring the Macondo in the Bombacaceae corridors. By integrating Macondo trees into the daily lives of commuters, the 50 meter tree becomes emblematic of flows, movement and most importantly, unwavering unity. Raised platforms could even elevate the Macondo to not only be placed on a symbolic and poetic pedestal but feature its elephant-like base at eye level. Pairing it with the undulating base of the Ceiba, the design of the plazas and parks could be seamlessly integrated, responding to the varying characteristics of the individual trees.

Dryfo Urbanism isn’t the traditional urban design of imposition over a territory, but a projective and responsive framework that simply highlights what is already there. By guaranteeing shade in mobility corridors and public space, Dryfo Urbanism provides a framework for those who are forgotten and cast aside. Informal settlement will inevitably continue to sprawl, but providing the critical needs every human is entitled to, is proactive design. Bringing the dry forest to the daily lives of each and every individual, Cartagena has the opportunity to blend nature and culture into one seamless landscape. A landscape where the two are no longer seen in opposition with one another, but in symphonic harmony.

Project| Dryfo (Dry Forest) Urbanism

Location| Cartagena, Colombia

Student| Ishaan Kumar, Landscape Architecture Graduate 2017

School| University of Pennsylvania

Professors| David Gouverneur and Maria Altagracia Villalobos

Image + Text Credits| Ishaan Kumar