Waterfront regeneration first became a major focus of urban design in the early 1980’s, prompted by the development of notable projects such as Battery Park City in New York, Pier 39 in San Francisco, Navy Pier in Chicago, as well as Vancouver’s waterfront. Since then, cities worldwide have leveraged their waterfront assets for economic development, steering industry away from their waterfronts to make way for increased public access and a broader range of economic opportunities. Today, after nearly 40 years of creating new models for waterfront revitalization, we have many examples of both successes and failures to guide us. So, what has the design community learned?

Think Big, Think Interdisciplinary. While design interventions along the water’s edge are invaluable—they create the character and experience of the water—without urban design and planning, many a waterfront sits empty, devoid of traffic and vibrancy. The beauty and elegance of design must pair with contextual planning decisions around the site and its relationship to the urban fabric, movement systems, and ecology.

Speaking of Ecology. Integrated solutions to improving the ecological health of waterways are never an afterthought. A robust understanding of watersheds, habitat needs for native plant and wildlife species, and opportunities for water quality improvements are all critical assessments that must be made in the planning process. The waterfront is but one component of a much larger natural system that must be considered in its full context.

Vibrancy for the People. Single-use development along the water’s edge limits the full potential of the public realm by making the water’s edge feel like a private amenity, which leads to underutilized waterfronts. The American festival marketplace model, focused on leisure, tourism, and retail uses is highly susceptible to economic fluctuations and require periodic reinvestment to keep them current and relevant. Take, for example, the Ports O’Call waterfront in San Pedro, now rebranded as the San Pedro Public Market, and Boston’s Quincy Market, which is also being repositioned. By contrast, the most successful waterfront developments go beyond creating economic activity along just the shore, they create real, connected places for communities to gather.

The Power of Great Design. Last, and perhaps most importantly, great design is vital to a great waterfront, as it synthesizes all of the systems, flows, and interactions between people, nature and the built environment to create places that are contextual and inspiring. Great chefs need more than just the right ingredients – they also need experience, creativity, and real chutzpah – to create a great meal. Design is much the same.

So how are those themes informing our own practice as landscape architects and urban planners? The following are three examples of recent work that attempt to create healthy, sustainable, accessible waterfront developments across the globe. Working with visionary private developers and cities, at Zidell Yards we expanded Portland’s public waterfront, we reclaimed Shanghai’s industrial waterway along Suzhou Creek, and planning helped redefine a city’s trajectory in our designs for Las Salinas in Chile.

Zidell Yards: Expanding Portland’s Public Waterfront

At Zidell Yards, in Portland, we worked with the Zidell Family, West 8, EcoNorthwest, Place Studio, and GBD Architects to restore and return one of the last undeveloped sites along Portland’s famed Willamette River back to the people. After a massive cleanup of the City’s largest and most complex brownfield, Zidell Yards will become the center of gravity for the South Waterfront District, which has grown into a major employment center anchored by the Oregon Health Sciences University.

With over five million square feet of new development planned, the neighborhood will integrate maker spaces, public art, and vertical farming into its mixed retail and residential plan. As long-time stewards of Portland’s waterfront, the Zidells advocated for direct water access for the public. Instead of developing the site to maximize potential, putting profitable high-rises right along the water, the team structured higher density parcels around tracts of publicly accessible areas to be activated by parks, plazas, and art. Once complete, it will be one of Portland’s only waterfront areas giving direct public access to the water.

Las Salinas: An Urban and Ecological Transformation

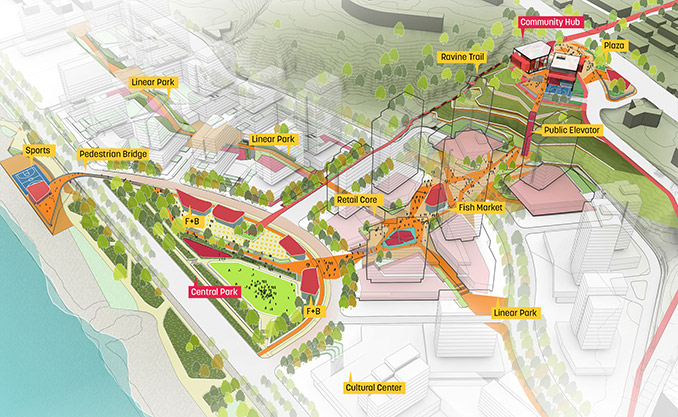

At Las Salinas in Viña del Mar Chile, our ambition was to reveal the true potential of a post-industrial site situated between a steep hill and the ocean—rethinking development practices in the city along the way. We could only accomplish this by transcending the boundaries of the site to think about ecology and connectivity, with immense collective efforts on the part of the community, client, and design team. Created together, this vision seeks to restore local ecology and re-engage the community to its seafront and public spaces—and is truly a shared vision to regenerate the vitality of this city.

Key features of the plan include, a new public elevator spanning 100 feet (30m) to connect a neighborhood to the sea; community trails; the most significant new public space in Viña; carefully articulated towers that minimize disruption of views; street level activation that maximizes commercial viability as well as urban quality; and an ecological framework plan enhancing the hillside landscape and increasing habitat connectivity and biodiversity.

The plan envisions restoring this waterfront neighborhood as an accessible and welcoming place for a broad swath of the city’s diverse population. This approach balances both real estate and civic value, which in the long-term positions Viña del Mar to maintain and grow its reputation as Chile’s forward-looking Garden City by the sea.

Suzhou Creek: Reclaiming an Industrial Waterway

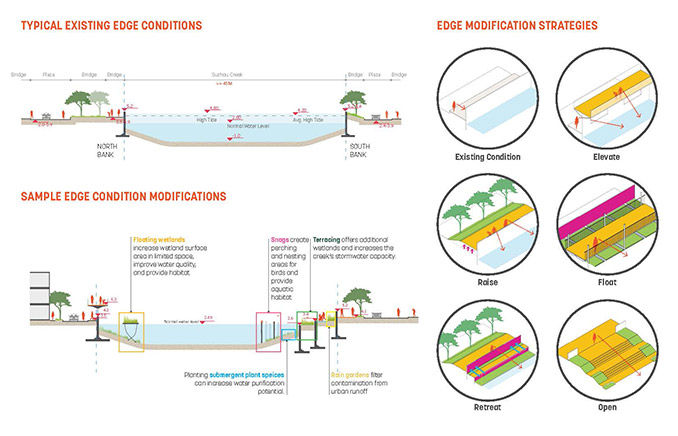

What began in 2016 as a competition seeking strategies for rethinking the 12.5 linear kilometers of the immediate edge conditions of Shanghai’s Suzhou Creek evolved into a design challenge that thought more broadly about the creek’s role in an evolving city. Recognizing the opportunity to unleash Suzhou Creek’s potential as the identity of a new district, the team recommended expanding the perceived waterfront of this newly reclaimed industrial waterway into the urban blocks adjacent to the creek.

By expanding public spaces around the river, giving reprieve to the area’s high density development, the plan creates a more cohesive pedestrian experience along the waterfront—one that is anchored by key public spaces throughout. New pocket parks alongside the creek and within existing neighborhoods are spaced no more than 500 meters apart, responding to the city’s long-held desire for more vibrant, community-oriented open spaces.

The restoration of Suzhou Creek as a vibrant public amenity unquestionably benefits the human experience by providing access to open space in the center of the city. But with the new plan also came an ecological opportunity that had never before existed along the industrialized waterway. Floating wetlands increase the creek’s wetland surface area in limited space, improve water quality, and provide habitat. Terraced wetlands alongside the creek increase the watershed’s stormwater capacity, while rain gardens on the adjacent roadways filter contamination from urban runoff. Submergent plant species add another layer of water purification and aquatic habitat, coexisting with strategically placed snags that offer perching and nesting opportunities for birds.

A New Model

The ideas around ideal waterfront development, which have been percolating over the last several decades, are manifesting fully in today’s plans and designs. Projects like our own work in China, Chile, and the United States and a sea of new projects across the globe are creating vibrant, contextual, and long-lasting waterfront spaces for the 21st century. As cities continue to embrace their waterfronts, this new model, which encourages a measured approach to real estate development, cultivates a lively public realm day and night, embraces ecology, and emphasizes connections back into the city fabric through powerful planning and beautiful design, will continue to bring waterfronts to the people, and people to the water.

Creating a New Model for Waterfront Revitalization

By James Miner, Dennis Pieprz and Michael Grove from Sasaki

Image Credits | Sasaki