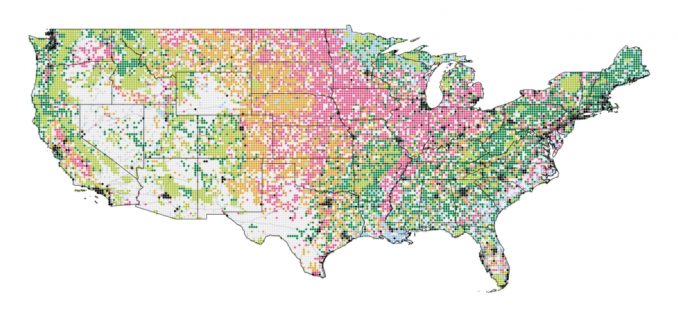

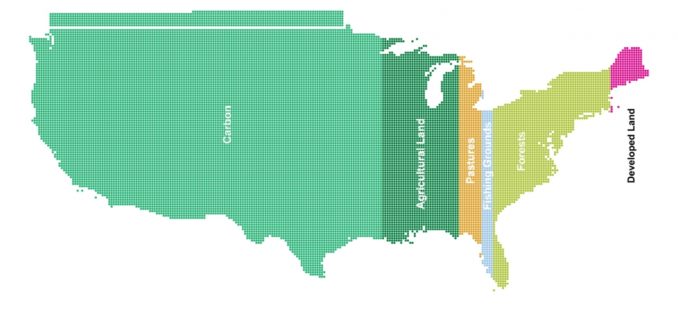

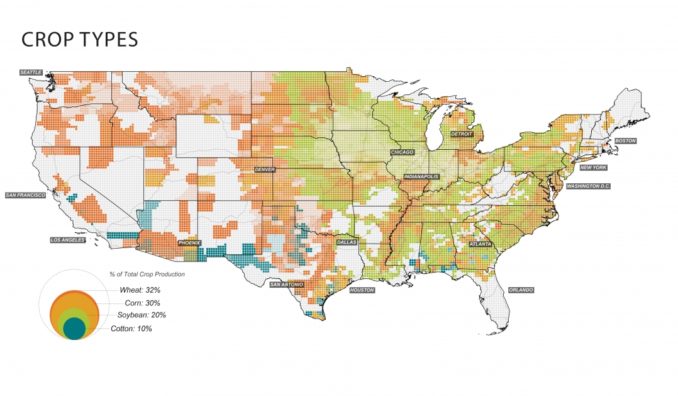

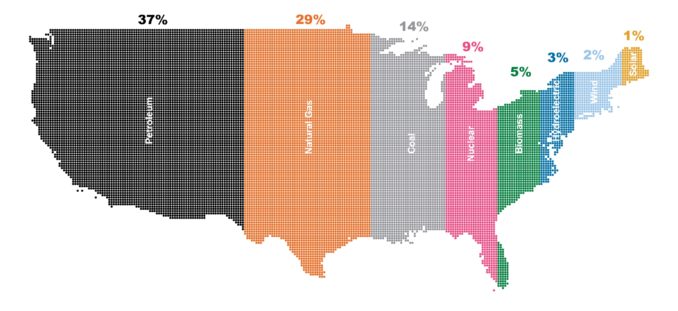

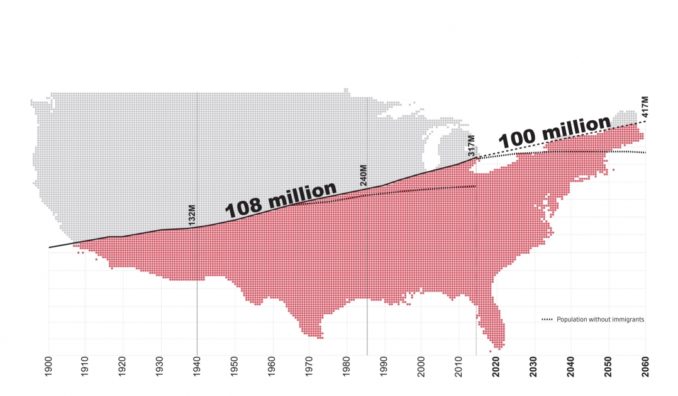

The Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology recently published An Atlas for the Green New Deal that was conceived in relation to three intersecting issues. First, excess carbon in the atmosphere is changing the world’s climate; sea levels are rising, temperatures are increasing, and destructive weather events are becoming more frequent. Second, because our systems of extraction, production and consumption are causing climate change, an incremental approach to the future is not an option. Third, the US population is expected to grow by at least 100 million people this century, adding significantly to what is already the world’s most consumptive, high-carbon economy.

Taking on these challenges requires that we ask some big—and unsettling—questions. What will be lost—economically, culturally, psychologically, physically—should the climate crisis continue unabated? How can we begin to come together around a response to the crisis that will reshape how and where we live? How can we begin to think about investments in the built environment as a catalyst for the broader aims of decarbonization, adaptation, and social justice at a meaningful scale?

The Green New Deal does not pretend to have all the answers, but it’s a bold and necessary start. Because it connects social change with environmental change, and because it recalls the ambitious spirit the original New Deal, the Green New Deal is the only set of ideas on the table that are scaled to the challenges we face. If realized, the Green New Deal would revolutionize our systems of production and transform how and where we live. If realized, the Green New Deal would enable us to not only adapt to climate change, but to also mitigate its root causes.

But right now, the Green New Deal is embryonic, represented only in the most abstract set of goals outlined in H.R. 109. Its outline of a sustainable future needs to be filled in. It needs to be developed, debated and designed. To that end, this Atlas for a Green New Deal brings together a vast and disparate array of information in the form of maps and datascapes; tools to help us understand the spatial consequences of climate change—not so that we may be frightened by them, but so that we may be mobilized around a response to them.

An Introduction to Our Atlas for the Green New Deal

Certainty is on the tip of every climate activist, scholar, and writer’s tongue these days. We are certain we have only until 2030 to rapidly decarbonize the economy. We are certain that even if we do manage to meet this ambitious goal, sea levels will still rise another foot or so—demanding that our cities do the same, or that their people are relocated, out of our shifting shoreline. We are certain things are getting worse—promised, even, that they are somehow worse than we’ve imagined.

We are certain, in part, because we have so many damn models telling us so many damn things about our now certain damnation. There are physical models of the Earth’s systems, showing how we can expect our oceanic and atmospheric forces to change under the various emissions-based scenarios developed by the IPCC. There are projective models of who might be displaced—and where they might go—as sea levels rise, temperatures increase, and the climate refugee crisis becomes impossible to ignore. There are predictive models of how various forms of climate adaptation might perform, often as instruments of flood risk mitigation. There are financial and economic models of how we might pay for a set of planetary transformations like decarbonization and adaptation. Increasingly, there are also simulation models of what it might mean to geoengineer the Earth’s systems, either by spraying sulfates into the stratosphere or by rapidly deploying negative-emissions technologies that remove carbon from the atmosphere. We have seen the future, and it works—so long as the assumptions in our models are set just right.

Each model brings a new degree of precision to the lucidity of our climate imaginary. They help us make sense of which outcomes are probable, which are possible, and they imply their own ideas about desirability in the process. And that winnowing of potential futures and choices can bring with it a sense of heightened certainty about how, when, and where things might unfold on a planet devoured by unfettered capitalism.

Though these models are an important tool for understanding how the future could or should be made manifest, they are not the only tool—even if we (designers, journalists, broader publics beyond the climate science community) tend to treat them as such. We do this despite the vast degrees of uncertainty in even our most basic physical models, to say nothing of our inability to model and imagine the socio-political, technical, and economics forces that will, ultimately, determine how much warming, mitigation, and adaptation we live with.The climate crisis is existential, replete with uncertainty, happening all around us, all the time. Though we have mapped it exhaustively here, maps alone cannot tell this story. We need more tools—for making sense of the climate crisis, for envisioning alternative futures that foreground what we might gain instead only what we’ll lose, and for stoking public imaginations and actions in ways that models, at least on their own, cannot. To paraphrase David Wallace-Wells’ apocalyptic book The Uninhabitable Earth, it is, we promise, better than you think. Or at least it can be.

This need for a more pluralistic approach to how we navigate and respond to the climate crisis is where The 2100 Project aims to land. Though physical, simulation, and socio-technic models of the future will always be an important part of this conversation, our intervention with this project is not about building precise models a future world reshaped by varying degrees of carbon emission. Rather, it is about backcasting—a method of scenario modeling that begins by developing an ideal outcome or future, and then works its way back from there—as a way of understanding a different set of potential futures; ones that may or may not be captured in these models.

As the authors of the first installment in The 2100 Project, An Atlas for the Green New Deal, we became interested in assembling this phase of research for three primary reasons. The first relates to the idea of backcasting as it pertains to the principal historical analogs of the Green New Deal: FDR’s New Deal and JFK’s Moonshot. We remain convinced that the window for massive, national-scale action on climate will open again soon, and we aim to use this project as a vehicle for generating new research into how those transformations might unfold. The second rationale for constructing this atlas is tied to the paucity of spatial expertise and imagination within the current Green New Deal movement. Though it has necessarily been led by organizers, economists, policy wonks, and others, the Green New Deal would transform how and where we live—it would revolutionize our buildings, landscapes, and public works in ways that have yet to be conceived. The Green New Deal is the biggest design and environmental idea in a century. As faculty and graduate students in a world-renowned school of design, we feel an obligation to engage in the Green New Deal along these lines. Finally, we felt compelled to assemble this atlas and to launch The 2100 Project in part because no one else has put anything like it together—all of the spatialized climate, land, and people-related models of the future in one place, synthesized and tightly curated, contextualized and coherently packaged together as an Atlas for the Green New Deal. And we also felt compelled to use this project as a way to critique the notion of precision and certainty embedded in these models by representing them through pixelated maps. After all, the future is fuzzy. Our models should be too.We are convinced that a window for national climate action will open again, forced ajar by young climate activists, which allows for the mass mobilization of resources called for by the Green New Deal. And when it does, we hope to find ourselves in a better position than we did in 2009 when the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA, also known as the Obama Stimulus) passed. ARRA required that investments in the built environment be tied to shovel-ready projects—the kind of string that sounds reasonable, until you realize that the only shovel-ready projects at the time were those that had been sitting on the books for years, unbuilt largely because they were bad ideas that no one wanted. We don’t expect to develop all, or really any, of the projects a Green New Deal might build instead on our own. But we do hope that this project can serve as a platform for others to do so.

We’re constantly told to go slow, think small, and tweak systems rather than transform them; that we are doomed, and all that’s left to decide is the extent of our collective destruction. But the Green New Deal offers something more—a chance to go fast, to think big, and to transform the structures that gave us climate change and inequality; and an opportunity to imagine a world in which things are, we promise, better than you think.

An Atlas for the Green New Deal

Published by The Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology

University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design