Strijp S is the former factory site of the old Philips-complex in Eindhoven, the Netherlands. The 27 hectare large area, which is the home of a considerable amount of monumental buildings, provided work to housands of people between 1920 and 2004. Even though the complex was surrounded by living neighbourhoods, Strijp S was always known to be a ‘Forbidden City’: an immense area, inaccessible to the unauthorised. In 2004 Philips sold Strijp S to investor Park Strijp Beheer, who will be redeveloping the area in different phases to a unique living and working environment, while respecting the original character of the remaining constructions.

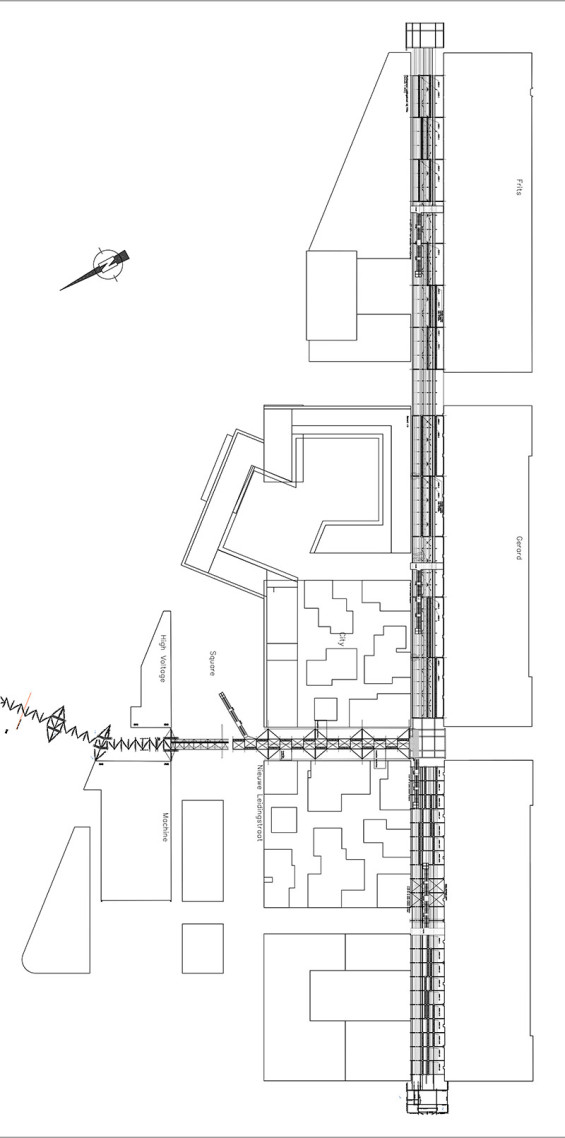

One of the most typical elements of the complex is the ‘Leidingstraat’, literally ‘Pipe Street’. A vast network of pipes and tubes – on top of the monumental steel constructions – transported gas, water, liquids and electricity to the factories on site. The pipes measured many hundreds of meters, and connected numerous buildings with eachother on the height of more than 10 meters. The redevelopment of Strijp S resulted in the demolition of a large part of the steel construction: only at the buildings of the Hoge Rug (‘High Back’) a part was kept intact.

The factory buildings of the Hoge Rug are impressive monuments, where Philips used to produce numerous types op devices. Developer Trudo transforms this area to a unique place to visit, work and live. The starting point for the project was to keep the original, industrial atmosphere of the Leidingstraat, and breathe new life into it.

Team and concept

In 2012, Trudo asked Piet Oudolf (well known from the Highline in New York) to redesign the Leidingstraat. Oudolf teamed up with Har Hollands, Deltavormgroep and Carve – every member focused on a specific part of the design. A continuous dialogue during the process resulted in fine-tuning all design elements: the plantings, public space, new steel constructions and the lighting design. As such, the patterns and rhythms, derived from the existing construction, are repeated and reflected in the new design. The design

deliberately shows that new elements were added to the existing construction, as a new contemporary layer that appears to be part of a temporary addition.

Public space

The public space of the Leidingstraat stands out from its surroundings because of the materials that were used. The design, by Deltavormgroep, consists of large, concrete elements that have a temporary feel, referring to the site’s industrial past. The robust slabs, in two different sizes, emphasise the long stretch of the Leidingstraat. The line pattern of the joints, on the other hand, corresponds to the overhead network of pipelines. On strategic locations the slabs are stacked on top of each other, creating sitting elements, steps and display plateaus. This, additionally, creates open spots in the paving of the Leidingstraat, which are planted with special vegetation.

Stairs, lookout platforms and planters

A second addition to the Leidingstraat are planters, lookout platforms and stairs, designed by Carve. These new steel constructions are independent units that are placed in between and on the existing construction. The stairs lead to the buildings Erik, Anton and Frits via the third floor, creating a second and elevated pedestrian connection within Strijp S. The platforms in between are also viewpoints, enabling visitors to overlook the immensely large Leidingstraat. As an answer to the existing monumental construction of the Leidingstraat, the paper thin stairs unfurl like net curtains downwards, wedged between the original pipes and tubes. Using as little material as possible, the stairs bridge a height difference of 12 meters. All new steel constructions are painted in a light grey-blue, which relates to the existing construction, the white facades of the Hoge Rug and the skyes above Strijp S.

The planters are designed as hollow bridge girders, spanning a total width of 21 meters between the trusses on the main load-bearing structure of the Leidingstraat. As the planting containers can only rest on the main construction – which differs at each building – every part of the Leidingstraat has another length of planters. Because of this, the containers vary from 7,5 to 21 meters, creating a pattern that mimics the different constructions of the Leidingstraat. Additionally, the hanging planting corresponds to the wild vegetation on the ground.

A special location is the ‘Node’, where the Leidingstraat used to connect to the Klokgebouw (‘Clockbuilding’).This crossing is still visible, but the pipes between the Leidingstraat and the Klokgebouw dissapeared when the buildings were demolished. As a consequence, this part has been reconstructed as the main load-bearing construction of an embranchment of the Leidingstraat. In the future, the crossing will regain importance as a junction in the elevated pedestrian connection. The design anticipates on these plans by already creating planters in the first phase. In the future, these containers will be integrated in the elevated walkway: the intended pedestrian bridge will act as an additional connection to the apartments of the future housing blocks.

Vegetation

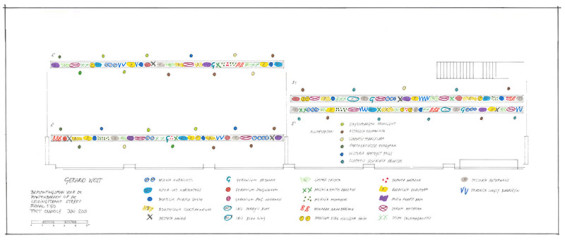

Piet Oudolf was, apart from supervisor, responsible for the design of all vegetations. The plantings interpret the new function of the Leidingstraat as a ‘City-Berceau’. Gradually, on and underneath the Leidingstraat a wild, non-cultivated landscape emerges, as if the seeds were taken there by the wind. Underneath the steel construction, where there is only little sunlight, characteristic shade plants will be growing. Additionally, multi-stemmed, low shrubs contribute to the sturdy character of the zone. The planters on top of the pipes and tubes catch more light, which allows for a different interpretation. Here, Oudolf designed hanging vegetations, which creates a thin ‘curtain’ that will hang down between the pipes, with a different play of colours every season.

Lighting

A fourth important aspect of the new Leidingstraat is the lighting scheme. The 550 meter long construction of the Leidingstraat and the former transport of gases and liquids was made visible by a dynamic lighting design. The pipes are lit from underneath in random segments using LED strips, of which the intensity and colour can be regulated. By varying the lighting intensity in sequences, lighting patterns in varying speeds can be generated on the length of the pipes. Also the disused sodium armatures of the Leidingstraat will be highlighted as a reference to the former industrial landscape.

In addition to the metaphorical lighting the pedestrian area underneath the Leidingstraat will have a basic lighting scheme in cool and warm shades. The lighting of the different elements, like the pedestrian area, seating elements and vegetation, can be regulated as to achieve the desired accents and intensities. Additionally, the stairs and terraces are lit by LED strips, integrated in the handrails.

Temporary Programme

Like in the era of Philips, the Leidingstraat remains to be the carrier of technique, temporary installations and objects. In the first phase so-called ‘bird-swings’ were installed in front of the Ontdekfabriek as a ‘kickoff’ project. In the future, also other temporary elements can be added to the structure – the possibilities are endless.

Attraction

By adding a new (green) layer to the construction, it shows that Strijp S has been transformed to an areawhere one can live, recreate and work in an outstanding way. Ten years after the start of the project, Strijp S – once a ‘forbidden city’ – is the creative and cultural heart of Eindhoven, the focus of the yearly Dutch Designweek and numerous other cultural events.

Strijp S | Eindhoven, the Netherlands | Carve

Design: 2012

Completion phase 1: 2013

Team: Carve, Deltavormgroep, Har Hollands, Piet Oudolf

Client: DNC Vastgoed

Photo credits daytime: Carve (Marleen Beek, Jasper van der Schaaf)

Photo credits nighttime: Igor Vermeer (www.vermeerfotografie)